March 31, 2016

JULIA ROX, CODY SMITH, DANIEL WEEKS

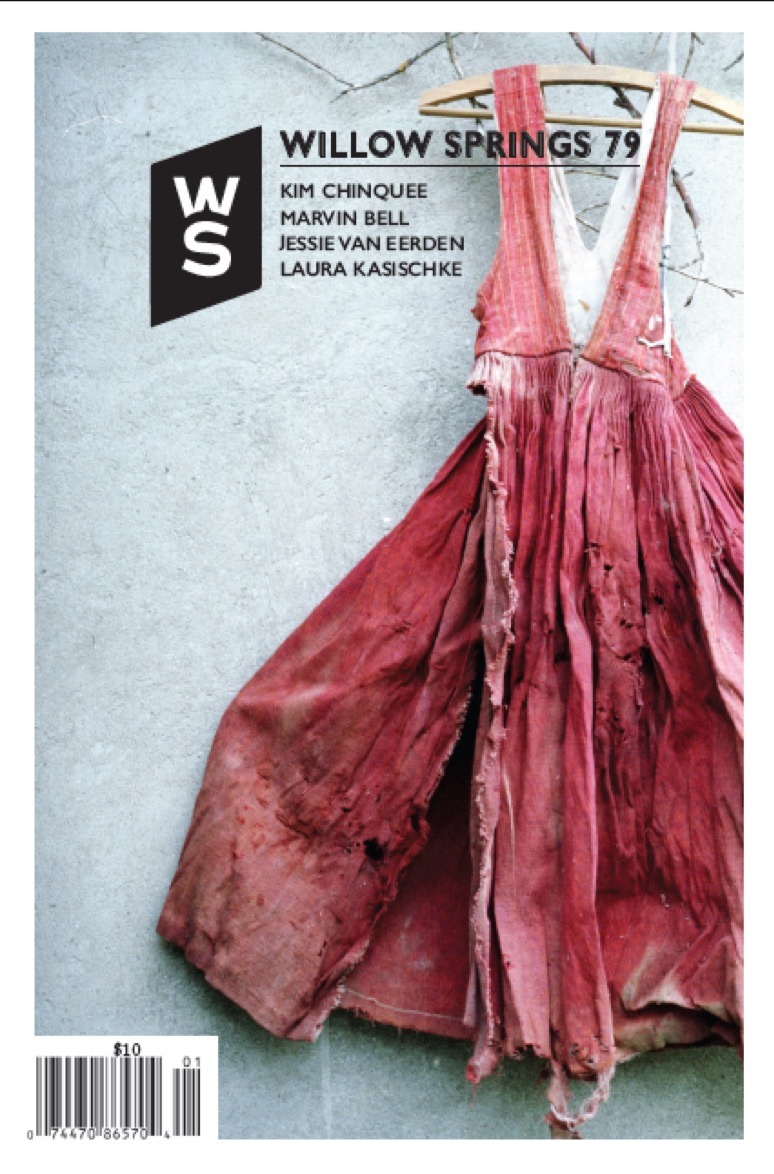

A CONVERSATION WITH LAURA KASISCHKE

Photo Credit: poetryfoundation.com

IN A REVIEW OF SPACE, IN CHAINS for the Kenyon Review, Jeremy Bass writes that Laura Kasischke “[posits] her readers in the space of active consideration, a space in which the reader might feel, as her poems do, actively alive in a world that is both fanuliar and strange, at once common and surreal.” Although Kasischke’s writing comes from familiar places—grief, illness, mortality—those places become transformed by her use of rhythm, space, and juxtaposition.

Laura Kasischke is a novelist and a poet, earning such honors as fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation. She has published ten collections of poetry, including Gardening in the Dark (Ausable, 2004), Lilies Without (Copper Canyon, 2007), Space, in Chains (Copper Canyon, 2011), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and The Infinitesimals (Copper Canyon, 2014). Her novels, some of which have been adapted into films, include The Life Before her Eyes (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002), In a Perfect World (HarperCollins, 2009), and Mind of Winter (HarperCollins, 2014). The board of the 2012 National Book Critics Circle Award called Space, in Chains, “a formally inventive work that speaks to the horrors and delights of ordinary life in an utterly original way.”

Much of Kasischke’s work explores the line between the mundane and the catastrophic. Apocalypse and mortality sit next to small, everyday moments, such as in “My son practicing the violin,” when the speaker observes that “Even the paper cup in my hand has learned to breathe.” Reading her poetry evokes the surprise and sudden recognition of something that has been on the tip of your tongue, something you haven’t been able to name until that moment—until Kasischke reveals an image or turn of phrase that feels exactly right.

We met with Laura Kasischke at the AWP Conference in Los Angeles, where we talked about existential terror, the Book of Revelation, and David Lynch.

DANIELLE WEEKS

Is there anything you’ve been obsessed with recently?

LAURA KASISCHKE

I have revolving fixations, and while this isn’t really poetry related, I’m obsessed lately with true crime. Because of the internet you can watch crimes committed and solved all the time. I think my obsession started getting bad with the Serial podcast. I’ve been working on a novel that’s crime related—a horrible murder that happened close to home. So now, with the novel, I’m not just watching crime on TV—I’m, you know, doing research.

CODY SMITH

Is there anything we can learn about storytelling from Serial?

KASISCHKE

There had to be a lot of manipulation there, excellent timing, and presentation with the backstory, but I think the strength of Serial is based on the strong material she kept chipping away at. There was probably a lot of jettisoning—boring interviews and other stuff she took out to streamline it. That’s key—getting lots and lots on the page so you have too much and can get rid of things. I used to say to students, “Just get it on the page. Worry later about the clutter, because it’s far better to have material to get rid of than pulling your teeth to find material.” Documentary filmmakers will say, “We shot 500 hours of footage to make this one hour film about starfish.” And you might think, what a waste of all those other hours. But it couldn’t have happened if they hadn’t had those things to take away. You could compare it to a stream of consciousness poem or novel. Sarah, the narrator in Serial, was not like the surrealists who said you could not revise anything. She revised and shaped and streamlined.

WEEKS

The critic Stephen Burt describes your poetry as suburban surrealism.

KASISCHKE

I like the surrealist impulse—which doesn’t necessarily have to be a dream landscape. I like association and the subconscious or unconscious mind being the source of inspiration. I grew up in a suburb and often go back there in my brain when I’m writing. I’m not trying to always return to the suburbs, but as a writer you only have so much material.

WEEKS

Your novel In a Perfect World is centered on a pandemic that leads to an apocalyptic world, and you have poems with apocalyptic themes. Is the apocalypse one of your obsessions?

KASISCHKE

In the novel, I was interested in asking, what if the Black Death happened now—if a third of the people died, or two-thirds? As for the poems, I don’t know why the apocalypse comes up. My parents weren’t super religious, but I took to religious stuff like a fish to water. I became much more religious when I was younger than either of them were, and I think it startled them, and they quit going to church just when I got most into it. I still have the Bible that was given to me for my Confirmation, and I completely annotated the Book of Revelation. I’ve always been interested in that book—the dream-like, surreal kind of crazy content. I used to know whole passages by heart. And I’ve always been interested in the Plague and the Middle Ages—the dance of death.

SMITH

Do you take any of your pacing or rhythm from the Psalms?

KASISCHKE

I think I was influenced by the Bible, yes—I really only encountered language like that in church. We didn’t have much poetry around, and I didn’t know there was a lot of free verse to be read. I had one poetry anthology and thought it was the only contemporary anthology in the world. Maybe I read the Bible because I wanted that experience of language. Until I got to college, I hadn’t encountered anything like Ezra Pound that I might have read instead of the Book of Revelation.

SMITH

I noticed your use of repetition in some of the poems in The Infinitesimals, such as the “Beast” and “Trumpet” poems. How does repetition come into play in the work as a whole?

KASISCHKE

I was looking at plates from this book at The Cloisters in New York, an illuminated Book of Revelation. I was looking at those images for inspiration, but the plates became less interesting than the descriptions of them: “Oh, there is a small bestial form.”I had different poems that came out of the same inspiration, so I gave them the same titles. A few of these poems were many-part poems. I pulled them apart, and they worked better separately, so I moved them around. I started to like the idea of many poems under the same umbrella of this title or description. After a while, if I did that long enough,I realized that every book could have the same title. Where do you stop? And honestly, that could be kind of cool, but I don’t know if it would’ve gotten published. Then people would really be asking, “Why do you have 50 poems with the same title? What happened?”

WEEKS

Do you see a difference in purpose between poetry and fiction?

KASISCHKE

I read poetry to see what other people are, how they can change my mind on something or excite me or startle me or inspire some sort of feeling in me or sense of mystery. I’m not the first person to say that poetry needs to be something done in language about something you can’t really do in language. You have that creepy, uncanny feeling—this isn’t a musical telling us something we could otherwise hear about. This is terra incognita. You can’t really go there in language, so the poet’s done the best he or she can to take us somewhere else.

For me, writing poetry is just about me. Not all poets feel this way, and that’s probably a good thing, but I’m writing poems to see what I can come up with. I think poetry is about expressing an experience or a memory or a possibility or something about the human condition you really can’t sit down and talk to anyone about.

Fiction can serve the same function. Mrs. Dalloway is my favorite novel, and I wouldn’t call that high entertainment or anything—it’s about the mind and about this weird place we inhabit. We find ourselves on Earth for a little while trying to figure out what we’re doing and what’s going on, but we spend most of our time trying to pretend that this isn’t all that weird—the fact that we’re going to die and that we have no idea when, and no idea if anything will happen after that. Even if we convince ourselves that we do think we know, we don’t have any proof. There are people who say we do, but we don’t. So, my God, we have to go around acting like it matters if we get to the dentist on time.

ROX

How do you bring freshness and surprise to your work?

KASISCHKE

With a few of my novels it’s been fun—but also frustrating—to start without a plan, just a landscape or character. As I’m writing, I’m figuring out what’s going to happen next, just the way you would as you’re reading a novel. It’s fun until you realize, three-fourths of the way through, oh, this has to be from a different point of view. I should have made a plan but I didn’t know what was going to happen, so how could I?

There’s that Robert Frost quote, “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.” I’m less interested in the reader’s surprise, though, and I think readers can be forced to be surprised by just inserting something surprising. The exciting part for me is the sub conscious—when I suddenly realize, oh, I wasn’t going to say that or maybe I shouldn’t have written that or I didn’t know where I was going but I’m going in the right direction anyway.

It’s easier to play out surprise in a poem because you work on it for a couple of days, then if it doesn’t go anywhere and you’ve surprised yourself by not writing a very good poem, you can throw it away. But if after five years you’ve surprised yourself by not writing a very good novel or one that makes absolutely no sense. . . . Well.

Even with the most formulaic writing, it’s all about the things you discover beyond your rational mind. In writing even the driest of essays, it’s the writing process itself that holds the surprise. Part of what’s fun is not putting on the page what you already thought and wanted to express but using writing as a way to figure out what you have to say. Once you start doing that, it’s all about surprising yourself.

And that happens every night in our dreams. You think, whoa, where’d that come from? Maybe it was something weird or startling or it seemed like someone else’s life, but it came from you. Last night, for example, I dreamed I had a cat litter box I was getting ready to clean. I saw the litter was moving and that something was coming up from underneath. I called my husband—I was freaking out, I don’t know why—and I made him watch. We saw this slimy head come out-like something being born out of there. I went running from the room, upset to see this mucousy baby coming out of the cat litter. After a while n1y husband said,”Oh, Laura, you need to look at this, it’s really cute!”I did not want to look, but I came in and there was a cute little kitten sitting on top of the litter. I was so excited! Where did that come from? The writing process can be like that—just sort of, whoa, where’d that come from? It comes from a part of our brains we don’t have access to when we’re not sleeping, dreaming, or writing.

WEEKS

A lot of your work has humorous moments even if it deals with death or medical recovery. How does humor work in your writing?

KASISCHKE

For a long time I was not interested in humor in poetry—I only wanted the darkest of material and tones. But then I realized I didn’t always want to read the darkest material. I think David Lynch helped me realize how much more morbid things can be when they’re leveled with humor, how they become even more startling and horrifying. When I watched Blue Velvet, I was like, oh, that’s it-that’s the tone you want. There are so many funny moments, like at the end with that robin chomping and chomping on a worm, in this really campy, disgusting way that’s hilarious. We laugh at that, but it’s still just horrifying.

WEEKS

In your poem “Twentieth-Century Poetry” you write, “Twentieth-century poetry-an eagle/in a cave, bleeding: such/a lot of noble suffering/in a dark and lovely place, full/of widows pleading.” Do you see a kind of violence in twentieth-century poetry or the twentieth century in general that must come out in poetry?

KASISCHKE

I’m sure if you looked at any century’s poetry you would see how it’s influenced by horror, but the twentieth century was really a house of horrors. I was reading an introduction to twentieth-century poetry and thinking about how laughable it was: Well, this poet influenced that poet and this poet influenced that poet, and just kind of tossed in there was the information that he died at Auschwitz and he killed himself after getting out of Auschwitz, and it’s like, oh . . . this says so much more than what the rest of the introduction to this anthology could really say.

ROX

You’ve referred to the “dead white men” in some of your poems—

KASISCHKE

Right. Wordsworth. I’m ashamed now, looking back. I knew nothing about Wordsworth. I didn’t like his name. I didn’t like the idea of there being a British poet named Wordsworth who wrote about daffodils. But did I know anything or had I read anything of his? No, I just assumed. Then I read William Blake and read about him and realized he’d lived a hard, horrible life and wrote some of the strangest poetry. I wanted poetry to be mysterious and weird, and he’s a British man who’s dead so I thought his poetry couldn’t be weird. But it is weird. This isn’t news to anybody except me for a little while.

WEEKS

Were there any dead white women who were influences?

KASISCHKE

I read women. But it’s a smaller group because they mostly lived and died without being educated, so they couldn’t write. This might be controversial to say, but when you’re a sixteen-year-old female who wants to write poetry, everyone hands you Emily Dickinson, and I didn’t really like her. I was like, she should have gotten out more. I don’t know. But now I’ve come around to seeing, at least, what every one says. But I don’t return to Emily Dickinson a lot. Sorry.

ROX

Were there other female poets who influenced you?

KASISCHKE

There were a ton of women just a little older than I was or who were still alive and writing—Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. In my own state there’s Diane Wakoski, and it was just flabbergasting to one in high school to think, here’s this woman who’s writing poetry in my state and she’s alive and she publishes it. It was her and Alice Notley who were introduced to me in college. But there were a lot of others, too, like Carolyn Forche. I was at the University of Michigan, so there were a lot of women poets coming through. I was in the residential college, which was kind of offbeat, and my poetry teacher was Ken Michalowski. He knew Allen Ginsberg and he ran a press and he knew all these beatnik or sort of political ’60s and ’70s poets. And he was an expert on the New York school of poets, so I was reading Denise Levertov. Anne Waldman came to the residential college and read her poetry. So, yes, there were a lot of women who influenced my poetry.

WEEKS

Women who write about domestic issues often get labeled as writers of”chick lit.” Have you ever felt you were treated differently as a female writer, based on the things you wrote about?

KASISCHKE

Not really—because of the readers I always wanted to have. I have nothing against men reading my poetry, but I’ve always felt that women might prefer it. I wish one of my novels would get called chick lit, because those sell. But, really, no. I probably lucked out in that way, being in the generation I was. Some of the women I’ve named who are ten to twenty years older than I am, they would be in a college or in a city where it was really all about the men poets and their sensibilities, and they fought that battle so that I could just write for them. In our MFA program today there are quite a few more women than men in every class, and I think sometimes it’s the guys who get, “Why are you writing about this?”

WEEKS

Are there writing rules or etiquette that writers force themselves to follow?

KASISCHKE

One of the rules I’ve always understood is that melodrama ought to be avoided. But I don’t want to write a poem unless it’s over-the top melodramatic. Really, I’m not sure anybody can follow any rules except the internal ones. I’m sure I had a teacher say, “Don’t be so melodramatic,” or “It’s too clever to have a little rhyme at the end like this,” but I don’t want to not have that.

I’ve been around long enough to see trends come and go. For a while, a ton of metaphor or imagery was just not where it was at—everything was more cool and abstract. Poetry fashions change. Some one does something that works, and we all start to imitate it. But then you move onto something that becomes a reaction against that first style. All you can really do is develop your own voice and write about the things you’re obsessed with.

Everybody says to write the kind of poem you want to read. I think about that a lot, and sometimes it’s upsetting, because I think I’ve just written exactly the kind of poem I don’t want to read. I mean really, right now, what I want to read are these mysterious short poems, and I don’t write them well. So I end up with another long, sprawling narrative poem, and I think, that’s not what I wanted to do. You make your own rules and just keep changing them.

What if you don’t allow yourself to write a certain way because you’ve heard it’s not the thing—it’s corny or sentimental or whatever, so you don’t write poems you otherwise would have written. Instead you’re busy trying to write a poem that’s not natural to you. And then you’ve lost those poems that might have been yours.

I’ve gone through periods where I was writing poems because I thought, oh, it seems like that might get published, and i would like to get published now, but they were such a waste, and I dragged them to the trash after long enough.

Maybe you have to go through a sentimental period or a melodramatic period where everybody will roll their eyes and you won’t get published because the work’s too heavy-handed, but maybe that clears the way for poems that won’t do that.

ROX

In an interview with The Smoking Poet, you described Dan Chaon’s process of “letting things mate.” Your poetry often makes amazing associative leaps that result in a cohesive poem. Is that a result of “letting things mate?”

KASISCHKE

I don’t really know. I have a journal, and I’ll write down something, but then I’ll start a poem that’s not really related to that. Later, I’ll find I can cannibalize that earlier material for the poem. Art is a process-oriented discipline. When things are going well and I’m in the process of writing a poem,getting to the end seems subconscious. There’s work I can do gradually. I know if I’m in the right place and I’ve got material and a journal or something that I can, you know, mate my other stuff with, then I’m sort of using the poem to think, and sometimes there’s a miraculously appearing ending, where different pieces come together. I find writing poetry very stressful for this reason. Maybe some people do it to relieve stress, but I find it stressful because I have to get into the place where the work’s not going to be necessarily rational. I have to be able to construct an ending that seems organic even though I worked hard to force the ending onto it. There’s nothing organic about it.

ROX

In your Willow Springs profile, you said you started writing the poem “Near-misses” with just the ending image of the spoon sliding into the soup. How did that poem develop from that image?

KASISCHKE

I think that was a case of ideas mating. I’d written that image down, and I wrote a little bit more of something, and then I wrote a little bit more, and I put them together and slammed down that ending. So that kind of “mating” does happen sometimes. That’s probably when it’s easiest to write a poem. Even if it’s a typo or you have this first line or you know this title or this last line is something you feel strongly about, and you just get the rest of it to mate. When Chaon talks about forcing things to mate, it’s like you’re writing and not writing a poem now. Hopefully, the things that come out of it have connections you can heighten. It’s sort of tricking yourself into being able to write. I think it’s good to study craft, but I don’t know if that word fits for me. I can manipulate line breaks and revise, basically, but that’s not really craft.

The whole idea of craft seems like being false. For me, poetry is more about improvisation. I think there are things you know, and maybe some attention to traditions and studying how other poets make something happen—but during the process of writing, there’s either a logical culminating moment or it’s a throwaway.

WEEKS

Has there been a time when you’re reading or writing and some thing feels false to you for that reason?

KASISCHKE

I’ve been trying to put together new and selected poems, and I’m looking at old books. Maybe other people, when reading a particular poem, haven’t really thought to themselves, ugh, this is no good. But I can’t even look at some of these poems, because I know I faked it a little—that the whole impulse was wrong. It’s like relationships you look back on and think, oh, that was just . . . I was in that for all the wrong reasons. You don’t want a lot of evidence of that past lying around, but with poems you can’t burn the photographs—they’re always there.