April 19, 2008

Terrance Owens, Shira Richman, and Tana Young

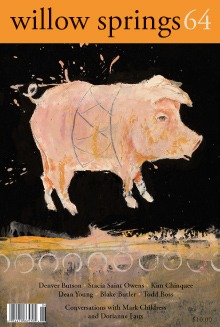

A CONVERSATION WITH DORIANNE LAUX

Photo Credit: alabamanewscenter.com

Dorianne Laux is the author of four books of poetry. Her most recent collection, Facts about the Moon (Norton, 2005), was the recipient of the Oregon Book Award and short-listed for the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize. She recently published a chapbook called Superman: The Chapbook, and co-wrote, with Kim Addonizio, The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasure of Writing Poetry.

Laux says of her poems, “It’s really important to me for people to understand what it is that I’m trying to say. On the other hand, I don’t want to write simple poems. I want to give people something really meaty to chew on.” Her poems balance the complexities of life with an understanding of the emotions of ordinary people. In her poem, “Facts about the Moon,” she writes, “The moon is backing away from us / an inch and a half a year. / That means if you’re like me / and were born around fifty years ago / the moon was a full six feet closer to the earth. / What ‘s a person supposed to do?”

Born in Augusta, Maine, in 1952, Laux worked as a sanatorium cook, a gas station manager, a maid, and a donut holer before receiving a BA in English from Mills College in 1988. She is known for poems of personal witness and for writing about everyday experiences. A review in the American Poetry Review referred to her book, Awake, as “Gutsy in its use of daily practice, daily grief and joy. Dorianne Laux’s Awake is one of the best first books I have ever read. These are poems of remark able maturity.”

Awards for her work include a Pushcart Prize, an Editor’s Choice III Award, and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Awake was nominated for the San Francisco Bay Area Book Critics Award for Poetry and her second book, What We Carry, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Laux has taught at the University of Oregon, and now lives with her husband, poet Joseph Millar, in Raleigh, North Carolina, where she teaches at North Carolina State University. We met at the Spokane Club where Laux peeled an orange and discussed pop culture, jazz, and the beautiful arches built by termites.

TANA YOUNG

It seems that much of your work is autobiographical. Am I correct in reading it this way?

DORIANNE LAUX

I’m a poet of personal witness. I know there’s a lot of feeling out there that the “I” is dead and the reader is a void, but I feel I’m talking to somebody. I don’t know who it is, but I’m talking to them, and I’m telling them about my experience of being alive, hoping that experience somehow translates or touches someone else’s experience of being alive. So yeah, it’s almost all autobiographical. There are moments when I shift things, and of course memory is faulty. And then on top of that, you’re translating what you feel in your heart and your guts and spirit, trying to translate those things into language, which is already an impossible task. It’s all a pastiche, but it’s true to my experience—as true as I can make it.

YOUNG

There’s a contrast between the idyllic sense in the poems you’ve written about your child and the difficulties described in the poems about your own childhood . What do these poems tell us about your journey?

LAUX

I came from a dysfunctional family as many of us do. My experience is not that different from anyone’s, it’s just that people don’t tend to talk about it because it’s embarrassing, or shameful, or complicated. Too complicated. Like somebody innocently asks, “Hey, do you visit your parents?” Well, it’s just too complicated. So I might say, “Sure, yeah, it’s fine. I have a wonderful relationship with my parents,” or my siblings, or whatever.

My parents’ generation wanted things to be economically better for their children. They worked hard to ensure that their children didn’t have to work as hard as they did. I think my task was not so much to make things economically better for my child, although that was certainly a goal. But I was also trying to make things emotionally and spiritually better for my child. And they were. So it’s still that American concept with a different slant, or a different set of goals. I wanted her to have a childhood that was free of all that. Of course, I didn’t protect her completely, and she didn’t have an idyllic childhood. You know, bad things happen all the time no matter how hard you try.

One might look at those poems and think, Well, this is what it’s like to have been a mother to this child. It was like that, and this poem is representative of this child’s life or this relationship between mother and child. And in fact, it’s one moment that’s been captured. I have yet to capture other moments, maybe, that aren’t as idyllic.

To me, poems in some ways are wishes. They’re asking us to look at what our best possible situation could be, so that we have an actual visual or aural representation of what we can work toward. It doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s like that. It means that we wish it to be like that, and so if we can somehow make that alive in language, we can actually make it alive in reality.

SHIRA RICHMAN

In your latest book, Superman: The Chapbook, you seem to be playing with the intersection of the ideal and reality. How did you choose to publish a chapbook at this point in your career?

LAUX

Well, it was wonderful in the way it came about because Joe [Millar] and I went to visit Redwing, Minnesota, where they have an artist colony called Anderson Center for the Arts, and on the grounds they have Red Dragonfly Press. Joe and I would go over every day to watch this wonderful guy, Scott King, work at his small press, and he has a couple, maybe three of these old, falling apart, beautiful, antique printing presses. He’s one of the few people in the United States who still makes type, actually forges the type, you know, casts it with metal.

We were just fascinated. We’d go over and watch him casting type and the hot metal pouring down through this little funnel and the letters coming out and he’s cutting them. We were hanging around all the time, bothering him. How do you do this? And how do you do that? So one day, he asked us if we would like to make a broadside. He said, “You can actually set the type yourself if you like.”

We went over and started setting the type, which was nor as easy as it sounds. There’s this big box with all the letters set up in this counterintuitive way, all the most used letters on the outside, and the least used letters on the inside. And so we’re trying to find the A and the L and also trying to make sure that the M and the N don’t get mixed up. We’d set the type, and then make an experimental plate of it and realize we had all the letters backwards and upside down. We’d have to start over. It took us hours and hours and hours to get these two little broadsides. The broadside I made was of “Hummingbird,” which is from Facts About the Moon.

After we made the broadsides, Scott asked me if I’d like to do a chapbook. He had created chapbooks for authors like Barry Lopez and W S. Merwin. He enjoys making these fine-press, beautiful little things and he wanted to know if I had a group of poems that I thought might work well together. And I said, “Sure.” So we worked on that for a while—he did all the work on it. I didn’t do any more typesetting.

Those are new poems, and it’s somewhat common for a writer to put together a chapbook of new poems that you wouldn’t get anywhere else, and the small press makes some money. All those poems will be in my next full collection, but they’ll be published in the chapbook first.

RICHMAN

Are the poems about pop stars indicative of a general direction in which your work is moving?

LAUX

Those poems were really influenced by reading people like Denise Duhamel, Tony Hoagland, these kinds of pop poems about popular culture. Among my poet friends, I’m the one they come to when they want to know about popular culture. They’re like, “Who is Bono?” [ Laughs.] Many poets, they’re just not hip to all this—”What’s Survivor?”—and I can tell them. “What’s Facebook, MySpace?” I know all this stuff. I don’t know why. I’m just a junkie for popular culture, and when I was growing up in San Diego, I loved all the popular music of the day.

So I thought, Why shouldn’t I write about these people I know? I grew up with Cher. I feel like I know her intimately. Why wouldn’t I write a poem about her? And Superman; I feel really embarrassed for how much I love Superman. No joke. When a Superman movie comes out, man, I’m right there. I want to see it. Of course I know that Superman is absolutely ridiculous. This whole idea of America—he’s going to save the world—it’s romance at its highest pitch. Yet there’s something moving about it, something very stirring about Superman. I’m not sure if this is where the bulk of the work is headed, but the poems were fun to write and will flavor the new book for sure.

YOUNG

Those poems feel like coming of age pieces to me. They take me back to the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, to those summers.

LAUX

Those were good days. They were also terrible days. Of course Superman is not Superman in that poem. He’s Superman with cancer, and he’s smoking dope, and he’s trying to stop the pain in his head, knowing he can’t save the world. He breaks my heart in that poem. But that’s how I see the United States in some ways, too. He’s representative of this culture, which is sick. It’s an interesting way to get to some material. Pop culture can influence art on a deep level. If you read somebody like Denise Duhamel or Tony Hoagland, you realize there’s something deeper going on underneath that surface. When you think about popular culture, you think immediately of surface. But what’s underneath? Like the whole idea of the Beatles breaking up, and what that public and highly contested division meant to a generation.

TERRANCE OWENS

You’re known for writing about ordinary people, but these pop culture references seem to go against that in a way, though they also connect ordinary with not-ordinary people—

LAUX

Well, Superman is as not-ordinary as you can get, and yet I make him an ordinary man. The same with Cher, who’s this huge diva-idol, but in my poem, she’s just a woman getting Botox treatments. So yes, I am dealing with a patently not-ordinary person, but I’m taking my vision and applying it to her. And of course, Cher is ordinary. If she weren’t ordinary, she wouldn’t be influenced by a culture that tells her she’s not beautiful. She’s scared. She doesn’t want to get old. She doesn’t want to lose her attractiveness, her sexuality. That’s what all of us are facing.

RICHMAN

David Wojahn said he thinks Americans have difficulty allowing the personal and the political to intersect, and that’s why there aren’t a lot of successful American political poets. What are your thoughts about that?

LAUX

I do think it’s difficult. Our definition of the political is complex. We think of politics as being what’s going on, for instance, in Iraq right now, or what’s going on in the government, or some issue like feminism, or something that we can put in a little box and say, “Here’s the issue, and here’s the person talking about the issue.” However, any time you ask readers to consider their lives, in any aspect, in any way, to consider their relationships to their children, to their lovers, their husbands or wives, to their jobs, to money, to power, whatever, you’re asking them to stop and think. That’s a political act, especially right now in America.

We’re having a hard time stopping and thinking. We’re having difficulty recognizing what makes us human beings. That we’re on the earth for a very short time. That life is precious. That death is on the doorstep—that’s a huge thing. You’re asking people to stop making widgets for a minute or two and consider what role they’re playing, not only in their lives, but on the large stage. Any art that’s political stops people in their tracks for a moment and asks us to consider.

So it depends on how you want to define political, and I think my poems are political in the way that I just spoke of. But it’s also true, more and more, I think, that they’re moving into a larger arena. On the other hand, I am not an overtly politicized person. I certainly have my ideas about things—and how I vote, how I move through my life has political implications, but I’m not, quote, a political poet.

In some ways, I think poets tend to be apolitical, because we are so open to possibilities, which makes it difficult to come down on one side or another. We see the complexities of things, so it’s difficult for us to say yes or no. We’re dealing with stuff that’s somewhere between yes and no.

If you said, “Do you think it’s right to kill people?” I would say, “No, absolutely not.” On the other hand, I suppose there are situations in which I’d have to reconsider that statement, while many people wouldn’t. They’re firmly on one side or the other. So is that political? I don’t know. In some ways you’re in Hamlet territory. To be or nor to be. You’re going to be asking yourself that question for the rest of your life. There are no real answers, and we know that. And poetry is a way of allowing a human being to live between those two ideas and feelings for a little while.

YOUNG

This reminds me of the encounter you describe in “S. Sgt. Metz,” in which you get to the person underneath the camouflage.

LAUX

The uniform, yeah, you could see that man in front of you and say, “Oh my God, what is this guy doing going to war? What an idiot. I hate everything about him, everything he stands for.” Or you could be on the other side of things, and say, “Look at this brave young man.” Both of those positions are simplistic ways to look at the human being standing there, trying to do the right thing, and you’re looking at him really trying to see who he is.

As an artist, I looked at him and thought, This is the perfect specimen of a male human being. The idea of him torn apart on the streets of Iraq was horrifying. To think of this beautiful human body, perfect in every way, put in front of bombs and gunfire was just unfathomable.

Maybe he’ll get through, you know? That’s the other thing, he’s a real person in the world. I never spoke to him. I just observed him, and I saw him talking to an older woman who was standing in front of him, jostling her bags, and he helped her. I could see that he was intelligent, kind, graceful. He was this human being living his life and that life was going to possibly be cut short for reasons I can’t fathom, and I don’t know if any of us can.

Humans are absolutely fascinating creatures to me, and I so much want to represent them in their dignity. We’re capable of miraculous things, and on the other hand, we are cruel, horrible, just horrible. I’m infuriated by humans and absolutely awestruck at the same time. We’re such fallible, fragile creatures. And this takes me back to my youth during the Vietnam War when I was saying, “The war is wrong. I’m burning these letters. I hate you. How could you do this?” It took me living for thirty or forty years to look at my brother and realize that was my brother I was hating. How could I have a brother who was killing people? How could I sleep with a boyfriend who was killing women and children? I was too young to recognize certain complexities that I’m now able to recognize. When I was younger, I thought, Oh, this is right and this is wrong. Now I realize I don’t know what right and wrong is. All I know is that human beings are gorgeous and worth preserving.

RICHMAN

Hearing you talk about Sergeant Metz makes me think of your poem, “Teaching Poetry with Pictures.” Why wasn’t that included in Awake?

LAUX

I know. Why wasn’t it? My editor didn’t like it. He said he just didn’t like it, so it stayed out. And now it’s gotten so old that I’ve never thought to put it in a book. I’d forgotten it until you mentioned it right now. I’ve written a number of poems that have ended up in anthologies or magazines but that never made it into a book.

There’s a little poem I wrote that was on the Portland buses called “Romance,” and it’s only a five- or six-line poem. I really like it, but it’s never made it into a book. It just hasn’t fit somehow. These poems are just sort of out there, but they’re not completely lost. You found one of them. Maybe it will make its way into a book someday. Who knows? Maybe somebody who has more time or interest or patience than I do will gather them.

OWENS

You said in an interview that “First lines are often important when determining the rhythm structure of a poem.” What’s the spark that first allows the rhythms to come in?

LAUX

It’s like music. When you listen to Glen [Moore], who plays jazz, and who I love to read with, he’ll just take a line, a piece of music, a musical phrase, and start playing with it. It’s basically—this won’t be worthy of an interview because you can’t transcribe it into the text, but it could be something like [hum s a jazz riff]. That would be the phrase, and then he goes [hums contrapuntal jazz riff]. And then you take that phrase and you start playing with it. That’s American jazz, the one thing we export that’s beautiful. Most of what we export is not so beautiful, mostly violent movies and fast food. But jazz is something we can be proud of. Now we take any rhythmic phrase and play with it.

That said, I do have a few rhymed poems. “Life is Beautiful” is an example:

Life is beautiful and remote, and useful

if only to itself. Take the fly, angel

of the ordinary house, laying its bright

eggs on the trash, pressing each jewel out

delicately along a crust of buttered toast.

Bagged, the whole mess travels to the nearest

dump where other flies have gathered, singing

over stained newsprint and reeking

fruit. Rapt on air they execute an intricate

ballet above the clashing pirouettes

of heavy machinery. They hum with life.

I can hear the music that I’m playing with, and the lines are approximately syllabic—between eight and twelve syllables per line, somewhat dactylic—beautiful, delicate, intricate. It’s also a rhymed poem: Useful/angel, out/toast, singing/reeking, intricate/pirouettes, and it’s end rhymed—all the way through, ending on “disorder,” and “gorgeous.” Not perfect rhyme, but good enough for rock ‘n’ roll. The poem posits a question: Maybe there are too many of us, and yet the other side is that we’re “gorged, engorging, and gorgeous”. Yes, maybe there are too many of us, but on the other hand, isn’t it beautiful? [Laughs.] Stuck between yes and no.

I grew up in a musical family. My mother played piano, so I was inundated on a daily basis with music. She would play everything from Beethoven, Bach, classical music to pop songs to musicals. She’d play from The Music Man, South Pacific, whatever the popular musicals were at the time. Also, I’d come home from school and say, “I heard this new Sonny and Cher song,” or, “I heard this Beatles song,” and she’d listen to it, pick it out on the piano, and play it for me. She could play anything. And everyone in my family ended up being musical, except me. I try to put it into my poetry.

RICHMAN

How did that happen?

LAUX

When I was first born, my mother divorced my father and went to California. She was a struggling, single mother and finally met my stepfather and was scared of having kids. When I was coming up, she played, but they couldn’t afford a piano. Later, she managed to get one and she started teaching the children. Well, I had already gotten past the rhyme of being taught piano. So, my sister after me, my sister after my brother, all of my brothers and sister’s kids play. I did play guitar, but I dropped it after a little bit and went to poetry. I think I took all that musical training into my ear. I could recognize a musical phrase and see how it could be played with to make it interesting.

That’s one of the things I start with. “Life is Beautiful.” I hear that word phrase as music. I love reading aloud because, to me, it’s like playing an instrument. All the phrasing is like singing. I feel like I’m singing; I’m just not singing. [Laughs.] But it feels like singing to me.

YOUNG

There’s a point at which one goes from being a student poet to a master poet. When you write, are you still pulling from a mysterious place?

LAUX

Probably 90 percent of what any artist does is practice. We practice and we fail and we fail. You set your pen to the page every day, and of course, you’re hoping that something grand will happen. But the chances are slim, and you know that going in, but you go in anyway. That’s faith. You keep hitting the page, hoping that something’s going to fire, something’s going to happen, something’s going to bloom out of it. And the more you practice, the more that possibility of success is present. The more you do anything, the greater the possibility that something might actually come of it. So you constantly live with failure, and yet, you know that that failure is teaching you something.

B. F. Skinner discovered this thing, intermittent reinforcement, where you can reward somebody at random intervals. It might be the third time, and the next time it’ll be the twenty-fifth time, and the next time it’ll be the first time, and the next time it’ll be the eighty-seventh time. You can’t know when the reward is going to arrive, but that’s what keeps you going. It’s going to come sometime. And that’s all I care about. I don’t care if it comes the hundred and fiftieth time as long as it comes, and it’s a very powerful thing. Any time you happen upon a poem, your spirit, your entire body, is filled with this energy of that magic that has happened, and you’ll do anything to get back to it. You’ll do anything to find it again.

I don’t worry anymore about writing. There are times that I go through dry periods. I never go through a block. I’m always writing, but there are times where I’m just not on my game, and I’ll use that time to read some new poets, go see some art, walk down to the river and just stare at it, or have a conversation with my sister, or whatever—do whatever it is that I do in my life, hoping that I’ll get filled up enough. And something will happen, some juggling will happen and boom.

Ellen Bryant Voigt has a great essay in her book The Flexible Lyric. I can’t really write about poetry. Some people are wonderful at it, like Ellen Bryant Voigt. I get lost writing about poetry. But she writes these wonderful essays, and in one of them she talks about termites—I think it is—how some people were studying termites. And they put them in a kind of aquarium with all their stuff they use to build these beautiful arches that make nests—dung and wood chips and whatever it is that they use. And she said the termites run around chaotically for a long time, and they have little pieces of this stuff in their mouths. Ultimately, one termite will accidentally drop a piece and another termite will drop another piece on top of it. And once that happens, they all get excited and run over and pick up chips and start making the arches.

When that happens, they all get alert and they’ll say, “Okay, it’s time to make an arch.” And I think that’s a wonderful metaphor for how we make poetry. We’re just running around in these chaotic circles with dung in our mouths, or wood chips, or whatever. And we drop something and then something else and suddenly this arch starts to appear. We really don’t know how it works. I think Ellen’s essay comes closest to describing how a poem happens.

It’s just this odd coupling of sound and image; our minds are so filled with chaos. Our bodies are filled with it, our emotions, our spirits are just chaotically running around, saying, “What, what? What, what, what, what, what?” And then something happens, and things start to make sense for a moment. Of course that’s all that it is, a moment, the moment of making the poem—and the moment of getting everything into its order is a beautiful, ideal moment. Then you go back to chaos, hoping for that moment again .

OWENS

That’s a good metaphor for jazz, too.

LAUX

Absolutely; that’s what jazz musicians are doing—riffing off a phrase, hoping that things will come together and build an arch of some sort. Of course an arch is a beautiful metaphor, right? There are termites on both sides, building their columns and they meet in the middle. And so you can think of that too as the reader and the writer. They’re coming together in the middle and touching.

YOUNG

Are there people you read that help get you in a state of mind for writing?

LAUX

Reading other poets is often what will spark my imagination. I’ll see one of their arches and get inspired. That doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll write a brilliant poem; it just means I’m inspired. It has to be both inspiration and something else that happens. I reread the poets I teach: Phil Levine, Ruth Stone, Sharon Olds, Li-Young Lee, Carolyn Forché, Lucia Perillo, Gerald Stern, Lucille Clifton, C. K. Williams, Yusef Komunyakaa, Marie Howe and Mark Doty, Tony Hoagland, another good essayist. Too many to list, but you get the idea. I love poetry that feels as it thinks. I’ve been memorizing Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale” and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Assault.” Those poems inspire me.

But lots of things inspire me. Travel—I’m really looking forward to moving to North Carolina, because it’s going to be a whole new landscape, a whole new culture, a history that I’m completely unfamiliar with, new people. All of this change is wonderful for a writer because you’re shaken out of your habitual responses.

We all get habituated, right? You get up in the morning, have your coffee, and read your newspaper, and that’s great. Everybody loves life in its mundane, daily aspects. It’s what makes us feel secure. But I also start to go numb a little bit and I don’t see what’s around me. So I put myself in a new situation and suddenly I’m really seeing the person next to me, hearing music, and I’m smelling, and I can’t help but want to write it down.

YOUNG

Do you have a particular time that you write every day?

LAUX

Some people are very disciplined, but everybody has their own way of approaching their art, and for me, because I started my writing life as a single mother and while working as a waitress, it wasn’t like I had an office and time every day that I could sit down and write. Life was too chaotic. So I got it when I could. When my daughter was off at school, I’d write. Sitting on the bench waiting for her to come out, I’d write. I’d be doing an errand, and I’d pull over to the side of the road, pick up a Jack in the Box bag, and write something on it. That’s how I managed to get poems written—in between times. I’ve continued doing that.

Whenever it strikes me, I sit down and write. Of course now I’m in a university, so I have all summer to write, which I never had when I was coming up as a poet. I have that time, and my body does sort of click in when spring comes. I can feel my body going, It’s getting to be writing time. Yeah. It does kind of get into these seasonal responses. Joe and I are going to the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts for five weeks this summer, and we’ll write every day.

I’m hoping I can start putting the new poems together and making them into a book. I need concentrated time to do that. I can write the poems between times, but doing the revision work—that’s the hard part. When you’re at a writers’ colony, you get up in the morning, have your breakfast knowing you have hours to write before lunch, and more hours after lunch and before dinner, and you can get a lot of work done. But most of the time, you’re just squeezing it in, and that’s fine with me. I’m happy sitting at a bus stop and writing a poem.

RICHMAN

Or at the airport.

LAUX

Yes, I started that Metz poem at the airport. I got halfway through it and my plane was called. I went down to Santa Cruz with my friend Ellen Bass and stayed for a couple of weeks. Ellen gave me an exercise. She said, “I want you to use these words, and these phrases.” So I went back to the Metz poem and used the exercise to help finish it, and I used all the words she’d given me. I’m grateful that I can write anywhere.

RICHMAN

Your attraction to capturing moments, is that why you don’t write fiction?

LAUX

I love people and psychology. I love stories, dialogue, relationships, description, everything that goes into making a story. But I also love compression and music. And of course our best prose writers do, too, but I’m much more interested in moments. I love reading novels and short stories, but as a writer, I’m not so interested in Fred getting from the living room into the car. I couldn’t care less. I want to go inside Fred’s soul and play there. Not that fiction writers don’t do that as well, but they’ve got all these other concerns. And I’m much more interested in the psychological moment , the moment of epiphany. I want brush strokes versus whatever is the opposite of brush strokes, which I don’t think there is an opposite. But that’s what I want to do. I just want those light feathery things.

But back to practical circumstances: I only had these moments in time to write because I had a child. I had to get the dishes done. I had to get the rag out, and the mop. I was writing in these tiny spaces and it’s difficult to write a novel like that. You could, but it wasn’t something that I had a whole lot of time for, so poetry was a great form. I could use all this stuff: dialogue, arc, character, description, and I could use it all in a very small space within a limited amount of time. While my daughter was at school, I could do this. Poetry was a practical issue for me. I could do a draft of the poem and then go off and come back and play with it a little bit and go away and come back. But more than practical, it was the fact that I loved sound. And fiction, novels, prose at its best does have that sound, but it’s a rare novel that ‘s musically beautiful throughout. It’s more often getting information out: And then she went to the store and picked up some oranges and a gun. It’s moving things along on a plot level, and I’m not so interested in plot. Reading plots, yes, but not writing them.

OWENS

You seem interested in meeting your readers in the middle, not making them walk across the whole bridge themselves—

LAUX

I grew up as a navy brat in San Diego, living in Quonset huts with bunches of other kids from all over the world, and those kids couldn’t care less about reading the back of a cereal box, let alone a book of poetry. Those are the people of my life. Those are the people I want to speak to, the people I grew up with, ran around in the canyons with. It’s really important to me for them to understand what it is I’m trying to say. On the other hand, I don’t want to write simplistic poems. I want to give those people something to chew on. And that’s a fine line, writing a poem that’s accessible, and yet has the complexity you feel it needs to be a true work of art. So yeah, I want to meet my reader, and I want mystery, but not misery, not where they’re throwing up their hands and saying, “What is this? I can’t understand it. What the hell’s going on here?” It may be out of fashion, maybe even a bit radical these days, but I feel strongly about being understood.