Found in Willow Springs 63

February 2, 2008

REBECCA MORTON AND SHIRA RICHMAN

A CONVERSATION WITH LYNN EMANUEL

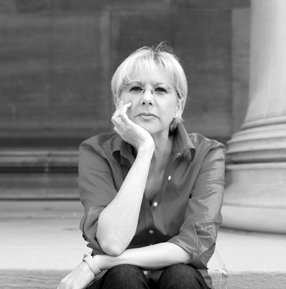

Photo Credit: Poets.org

Lynn Emanuel was born in Mt. Kisco, New York, and raised in a working-class neighborhood in Denver, Colorado. Surrounded by an extended family of artists, and raised by a businesswoman mother, Emanuel distills her early experiences into a potent cocktail, rewarding diligent readers with unpredictable, meticulously crafted, hyper-aware poetry. In typical Emanuel style, a poem about her dead father, “Halfway Through the Book I’m Writing,” moves in a startling direction: “‘What gives?’ / I ask him. ‘I’m alone and dead,’ he says, / and I say, ‘Father, there’s nothing I can do about / all that. Get your mind off it. Help me with the poem / about the train.’ ‘I hate the poem about the train,’ / he says.”

Of Emanuel’s most recent book, Then, Suddenly—, Gerald Stern says, “There is some Eliot here, some Stein. Emanuel carries self-consciousness to the shrieking edge—and almost falls in. Well, she does fall in. She is a master of the negative, but she doesn’t sigh in boredom; she yells in pain. Her vision is original; so is her language.”

In addition to Then, Suddenly—, Emanuel is the author of two other collections of poetry: Hotel Fiesta and The Dig. Her work has been featured in the Pushcart Prize Anthology, Best American Poetry, and The Oxford Book of American Poetry, among other anthologies. Her honors include the National Poetry Series Award, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Eric Matthieu King Award from the Academy of American Poets for Then, Suddenly—.

Emanuel earned an MA from City College and an MFA from the University of Iowa. She has taught at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Warren Wilson Program in Creative Writing, and the Vermont College Creative Writing Program. She currently directs the writing program at the University of Pittsburgh. We met in her New York City hotel room during the rush of the Association of Writing Programs 2008 conference, where we discussed comic strips, “breaking up” with Italo Calvino, and the culture of getting by in America.

SHIRA RICHMAN

Could you take us on the adventure of writing a poem, any poem you can think of, from its inception to how it grew, shrank, and found its own skin?

LYNN EMANUEL

It’s often a long, rather uncomfortable process for me. Right now, I’m getting another book together, and as I was gathering my work, I found a poem I had published in long-line couplets. I also found an earlier, longer draft, and I thought, Oh no, this is a much better version. Which I often think—that I remove too much material. So I went back and put the more substantial, longer version into the manuscript, and I brought it with me to New York, thinking I could read some new work. Of course, I looked at the draft I brought and thought, God, this is awfully wordy and long. The cliché about poems not being finished, just being abandoned, is particularly true for me. I never feel that a poem actually does reach the right form; it just reaches the form where I cannot bear any longer to change it.

Often it’s a process of scraping a lot of material away. I never write short poems. Never. The one short poem that Poetry published started out being much longer. I showed it to a friend and she crossed out everything but the last eight lines and that was it. I sent it to Poetry with a group of other things and that was the one they took.

I’m someone who carves things out of a larger block and then I feel the discomfort of having done that. Maybe I cleaned it up too much. Or maybe I’ve taken too much out. Or maybe I’ve diminished things.

REBECCA MORTON

Are you comfortable carving out a small piece of something longer?

EMANUEL

Well, it worked that time because I was a) so pressed for time, b) so fed up with that particular draft, and c) when I looked at what my friend did, I said, “Oh, that’s brilliant!” That was an extreme example. I feel both comfortable and uncomfortable writing that way.

The poet Bill Matthews was a friend of mine, and I remember him saying at one point, “The trouble is that it never gets any easier.” I think that may be especially true of poetry. The longer I write, the more difficult I’m finding it. Each book is different. I arrive at a moment when I have a certain number of pages and think, Okay, how do I put this together? I should know this, I think, I’ve done this. But each book presents its own problems.

One of the troubles is that as you get older, the expectation you have of yourself—that you know how this is going to work and you know how to do it—is actually something you have to battle against. When you’re younger, it’s all sort of scary, but you realize your book is going to be kind of a provisional form: You’re not going to achieve nirvana when you put this book together. You know you have other books down the road and you’ll get it right then. By the time you get to your fourth book, you think, Oh no, it’s never going to be… right. It’s always going to be like starting from the beginning. And you feel resentful. I do. I’m fifty-eight. I don’t like not knowing.

After my first book, what interested me were the ways in which the form of the book itself could be expressive. If I were a fiction writer, I would write novels. Never short stories. Giacometti said at the end of his life, “The only thing I care about is the feeling that I have when I’m working.” Which is a marvelous and unnerving thing to say. It’s wonderful, but it’s also like, And that’s it. I don’t feel I’m a great artist; I don’t feel inspired. That feeling while working was all he cared about. All I seem to care about these days is the larger unit of the book itself, the drama of turning a page, how I’m going to feel at the end, the unfolding of ideas and, often, narrative. I’m less and less interested in the work of perfecting a single poem. And though I work like a dog on that, in an odd way it doesn’t interest me. What interests me is the joining of the parts into something else. But I’m exhausted by it. Enough already; I want to be Steve Dunn.

The story I tell about Steve Dunn is that I was at a writers’ colony—I think it was MacDowell—and as I was walking out of my little cabin in the woods one morning, he was on his way with suitcases, and I said, “Oh, you’re leaving today?” He said he was, and I asked what he was doing until his ride arrived. He said, “Well, I have an hour left and my book is due at my publisher, so I’m going to assemble the manuscript.” And I realized that if you are Steve Dunn you can do that. It’s something I envy but can’t seem to do.

RICHMAN

So you’re not working on individual poems, you’re working on a group?

EMANUEL

It seems that I am. Always. Even when I pretend I’m not. My poems aren’t interesting to me until they’re part of a larger form of articulation. I’m interested in contradiction. I’m interested in saying something and then unsaying it. Or saying something and then inventing a voice that says, “No, that’s not at all the case.” If you’re interested in binaries and contradictions and conflicted versions of yourself and anything else, then maybe you have to be interested in the larger unit.

RICHMAN

I know you described Then, Suddenly— as a group of rebellions, such as the characters against the author and the author against convention. How much do you see the writing of that book as a rebellion against yourself and your previous work?

EMANUEL

Honestly, at the time I was writing it, I didn’t see it as being very different from my earlier poems. It was only in retrospect that I became aware that it was. I wish I could say, “Oh, yes, I was rebelling against my earlier work or I was re-seeing it or undoing it.” At the time, though, I didn’t realize that.

My father’s death came in the middle of writing that book, which was so enormous an event it swept away everything else. I remember Molly Peacock saying there was a time in her life when she was so sad and spiritually miserable that the only thing she could do in a poem was to get from one syllable to the next. And that’s how she became a formalist, which I always thought was a magnificent account of why it is that one might make a certain kind of choice in one’s writing. I think in an odd way that Then, Suddenly— was like that for me. I was just drenched in sorrow. The book had started as an investigation of my interest in movies and film, and the difference between sitting down and experiencing something on a page and sitting down and being moved by a film. That was going to be the subject of my book.

And then my father died. Then the issue of what it meant to be moved and be moving became an incredible heartache. I wish I could say that, at the time, I understood that this book was different from my others, but I didn’t. I just tried to get from one syllable to the next. I just tried to deal with grief and finish a book. I didn’t know how different it was until afterward.

MORTON

Do you think your concept of the book you are currently writing is different now than it will be after it’s done?

EMANUEL

There are writers who are much more articulate about what they are doing at the time they are doing it, and I seem to be someone who needs to undergo a generous period of self-delusion and think I’m doing X when all the time I’m doing Y. So I don’t really know.

I’ve written a series of poems in the voice of a dog, and I’ve invented an idiom for this dog. It talks a little like a cartoon. I began the poems when I was teaching for one semester at the University of Alabama. I felt I was absolutely outside of the English language, because all around me it was being spoken in a way that made me feel like a Yankee foreigner. Also, it felt like daily speech was much more engaged in the sort of—I don’t know—eloquence and figurative possibility. Everyday speech seemed to accommodate figurative language in a way that, when I was teaching my students or getting groceries in Pittsburgh, didn’t happen. So I felt clumsy and awkward; every time I opened my mouth, I was The Other.

This dog started to talk to me and it was a companion in clumsiness and awkwardness. The dog also became a figure for a kind of class—an underdog—and a whole landscape grew up around this character, a world of diminishment and poverty. So I think that’s going to be part of the book, but I don’t know quite how.

RICHMAN

It seems you’re often interested in the relationship between language and class. What are the origins of that interest?

EMANUEL

I always felt that The Dig was really about class and work and impoverishment and how those things impinge on women. That continues to be something I’m interested in. It comes from my own background. When I was growing up, there was a time when my mother and I lived on our own; we had few resources and little money. That kind of hardship is very very moving to me—to live in this culture just barely above the line that says you are really poor. Just kind of making it moment to moment. A lot of people in America live that way, and I think they always have.

Frankly, it’s one of the things I love about Gwendolyn Brooks’ poems. They inhabit that landscape so fully; they’re about the culture of getting by, especially her early work. I think that’s what this dog is all about. I was reading the New York Times this morning and one of the articles was about the dogs they rescued from Michael Vick. It’s sort of unreal, the cruelty that was visited upon these animals. But it’s not about the Michael Vicks. It’s about a culture in which an animal, domesticated so that it is deeply part of our lives, has such cruelty visited upon it. Sometimes a dog is not just a dog. Sometimes it is a symbol for how we mete out cruelty to each other and about the abuse of things that don’t have power. Women, dogs, poor people.

It was incredible to me when, during a discussion regarding ways to recharge the economy, someone in Congress said, “Well, let’s give people more food stamps,” and someone else said, “Oh, no, let’s not do it that way. Let’s do it another way.” I thought, How can it be that someone can say, “Let’s give people who need food more food or a way to buy more food,” and then someone else says, “No, let’s not do that,” and that is considered merely part of daily conversation? It flabbergasted me, that kind of cruelty. In some way, this whole thing about the dog is part of that, although the backstory will never make it into the book.

MORTON

In an interview a few years back, you said that one of the reasons you’re drawn to film noir is for its obsessiveness, the same image coming up over and over again. What are your current literary obsessions?

EMANUEL

Comic strips. It’s weird. My imagination has to be obsessively faithful to some muse. First, it was the muse of film noir; now, it’s the muse of comic strips. I’m fascinated with how, in a way, each panel in the strip is like a single poem, maybe a sonnet. The panel is a little box and an image and some language; it’s an extremely tight, circumscribed form.

I’m particularly interested in one by George Herriman, called Krazy Kat, that lasted from the twenties into the forties or fifties. There were three main characters: a cat and a mouse and a policeman. Herriman listened to immigrant language, to the language of people who were learning English, so the language of the strip was saturated with this fabulous nontraditional English. The language is itself a kind of character and landscape, and that really interests me.

That’s my current obsession. Can I get away with this? Can I create a sort of comic strip character, and do I need graphics? How do I wed a graphic element to the text?

MORTON

The image of the dress comes up frequently in your work. What does the dress mean to you?

EMANUEL

Clothes have their own life. They are symbols and icons, and people don them. They put them on, and they are read in a certain way. R-e-d and r-e-a-d. I think that one privilege of writing out of a noir aesthetic is that icons of clothing in film noir are very clear. There’s the bad girl and the good girl and the gangster. There’s a way the gangster dresses and a way the good guy dresses, and what kind of hats he wears, and the way the police dress. There are only about four or five possibilities. The palette is very limited.

Also, it seems to me an underutilized possibility. Why aren’t more people writing about clothes? Why can’t a hat or a dress be a symbol like a rose? Why are pieces of clothing a less legitimate series of symbols than other things? Why is clothing less legitimate than trees? In India, walking down the street, you can read people’s castes from their clothing, and I think that’s also true in the U.S. I don’t think clothing is any less legitimate than the natural world as a source for metaphor.

The same is true of food. Sometimes even I’m surprised by how much I write about food. It fascinates me. And I think that these subjects—food and clothing—are seen as traditionally feminine. You can be a man and write movingly about trees and water and flowers because Wordsworth did—although he stole a lot of it from his sister—but writing about clothing is typically seen as a product of the feminine imagination or of the “feminized man.” I think that’s one reason food and clothing don’t have legitimacy as a source for images.

RICHMAN

You grew up surrounded by all kinds of artists: dancers, sculptors, choreographers, and painters. Did you feel there were other possibilities for your life, or did you feel you had to choose among artistic pursuits?

EMANUEL

I had about as much choice as someone who comes from a family of lawyers and has to go into law. To some degree, it was not a choice. It was so all around me that another way of being in the world didn’t seem an option, even though my mother was a businesswoman. But she was a real pioneer. She was singular. There were not a lot of women who were serious businesswomen in the 1950s. So, that felt like an anomaly. It was an anomaly.

RICHMAN

Do you wish you’d had a choice? What else might you have done?

EMANUEL

Now I wish I had. [Laughs.] I don’t know what I would’ve done. The older I get, the more I feel that now I want to do something that’s more directly helpful to people. I would like to be an advocate for children in courts. The older I get, the more I think about how much more time I have. It’s great to write poetry, but I want something that’s more direct.

MORTON

Your last book, Then, Suddenly—, is so funny. Do you see risks in incorporating humor into your work, or do you fear that incorporating humor will cause people to take you less seriously?

EMANUEL

I have never had that fear. I always feel that my humor emerges out of rage and sorrow. There are different ways of being funny in books and different forms of humor. When you are part of a disadvantaged group, you often use humor as a way of getting back at the dominant culture.

I have never felt that I would not be taken seriously because of humor. I know this is something people talk about and a concern that writers have. Maybe I should be concerned about that. But I’ve always felt that in any book I’ve written there’s been enough gravity that the reader doesn’t just yuk it up all the way through. In Then, Suddenly—, my dead father’s voice comes in and says, “God, I hate this poem,” or, in another poem, “Who are you dating?” Maybe I’m wrong about this, but if you’ve experienced the death of someone close to you, that kind of thing is both extremely funny and just horribly hurtful. People die, but they don’t go away. They are still there and they visit you. So when the father in “Halfway Through the Book I’m Writing,” says “I’m alone and dead,” I find that a horrible moment that sort of balances the humor.

RICHMAN

Are there influences in your life that helped you hone your sense of humor? People who you saw or studied or learned from, or ways in which you were forced to use humor?

EMANUEL

I don’t think so, but growing up, I did see a lot of people in my family use humor as a way of keeping themselves afloat. Humor is like the ability to sing well. It’s a kind of pleasure you can provide for yourself that doesn’t depend on anything or anyone. You are able to provide your own joy and you don’t need anybody else to do it. Since I couldn’t sing, I think humor became that.

And I will say, now as I think about it—I can’t remember how old I was—maybe I was in my middle twenties when I met William Matthews at Bread Loaf. He was the most extraordinary talker. You would want to sit for hours and listen to him. He was so eloquent and funny, and his humor was often extremely cutting. I remember once when we were in New York, I was saying something about the influence of a well-known poet and Bill said, “Oh, yes, So-and-So likes everything from M to N.” It was perfect. He was absolutely right. That was the other thing about Bill’s humor, it was not only wonderful, but it was surgical. And after that, I could never feel bad again about So-and-So, because I would look at him and think, Oh, yeah, he likes everything from M to N. Bill inspired me. I learned from him that humor could be complicated.

RICHMAN

Once, an interviewer asked you, “So did you quit reading Italo Calvino?” and you answered, “Yes, it was like quitting smoking.” Why?

EMANUEL

Because, at a certain point, reading Calvino was a kind of addiction. I felt, Why should I write? Here’s someone who’s written every book that I would ever want to write. I must be him. I am totally unhappy in the world unless I can be reincarnated as Calvino.

So I had to stop reading him because there was no reason to be myself. In order to just get a book written, I had to stop reading him because he was one of those authors who—for me—seems perfect. Then, luckily, I discovered that he wasn’t perfect. I think there’s a lack of tragic vision in Calvino. It was marvelous when I found that out. Aha! Here’s your fatal flaw! You bastard, you had me in your clutches all these years!

All of my homages are arguments with poets. Walt Whitman, get out of here! Who can be an American poet? Nobody can be an American poet—you’ve already been every poet in the world. Every permutation of American poetry that we could possibly imagine, you’ve already done it. You’ve ruined us.

And Gertrude Stein. I mean, I love Gertrude Stein. Sometimes, I think there were these writers who were beamed down to us from more advanced civilizations and I think Stein may have been one of them—I’m sure Emily Dickinson was one of them—but it’s also true that Stein is sometimes just a typewriter. I don’t think it’s interesting to be someone who just worships Gertrude Stein, so I had to have an argument.

I had to have an argument with Calvino, which meant at a certain point I just had to say, “Okay, I’m turning you off. I’m changing the channel. No more Calvino. We’re breaking up.”

Actually, I hope it works. I’m writing an homage now to Baudelaire, and, by the way, he is the poet of clothing. And whenever I wonder, Why do I think it’s legitimate to write about women’s dresses? I read him. Of course, he was French and I’m not, but nevertheless—I absolutely have to break up with him now. He doesn’t know it, but… [Laughs.]

MORTON

What elements of your work are influenced by Stein?

EMANUEL

Here’s the thing: stylistically, aside from that one homage, “inside Gertrude Stein,” I don’t think there’s much influence. It’s not talked about often enough that one can have a lot of influences as a poet that don’t show up stylistically. I was influenced by the idea of her. I was influenced by the way she makes nouns and verbs and syntaxes into characters—she was beyond the pale.

I taught a course on the avant-garde with a colleague of mine, and nobody we read was as radical as she. So I love the idea of her and I love some of her writing—I love the way she critiques syntax, critiques the sentence—but I don’t feel therefore obliged to deracinate sentences because of Gertrude Stein. There are poets who do feel that way, and I admire that, but I seem to be able to be completely and comfortably contrarian in my writing. It doesn’t bother me. I can use conventional syntax and love Gertrude Stein, love her critique of conventional syntax, believe that she’s absolutely right—and still use conventional syntax. I would have no trouble being a collaborator during a war, I’m afraid. It wouldn’t occur to me that I couldn’t play both sides. Or I could easily be a double agent, the spy who spies both ways.

RICHMAN

That’s partly what relates you to Gertrude Stein, because I think of that as a sort of Cubism. And one of the things in Then, Suddenly— that’s so interesting is that, as a reader, you can go from poem to poem and never know what your role is going to be. It seems as though you’re examining the roles of reader, writer, speaker, and character from all these different angles and points of view.

EMANUEL

That’s exactly what it was. [Laughs.] I knew that! That’s wonderful. Perhaps you’re right, although I don’t think I understood it until you said it. I think you’re right. You don’t feel you have to remain faithful to a certain point of view, nor do you have to resolve the contradictions, nor do you have to, at the end, think, Well, okay, here, we’ve arrived here. I felt it was enough to simply present this reader, that reader, this speaker, that speaker, this author, that author, and that was the composition. That’s exactly the reason I’m in love with Stein.