MRS. SCHAFER IS GETTING FIT. Women don't lose weight anymore, or slim down, or tighten up. They get fit. This is all according to Mrs. Schafer's daughter, Jessica, who learned it from a man named Butch, who will soon become Mrs. Schafer's personal trainer. To simply want to lose weight is vain, apparently. Getting fit is about taking responsibility for yourself and your future. Ensuring more of the good years. It's about not becoming a burden on your children or society, as much as anyone can.

The gym is two blocks from Mrs. Schafer's East Village apartment, and though she's walked by it hundreds of times since it opened a year ago, she has never been inside until today. Today she put on a pair of old sweatpants and an oversized pipefitters union shirt that belonged to her husband. She also put on her brand new sneakers— garish, huge shoes as awkward and light as lifejackets, with swoops of color crisscrossing each other in imitation of what? Straps? Laces? But why imitate laces on a lace-up sneaker? The man at the Nike store had been unable to answer her. Everything, he said, was designed by scientists. As if that settled it.

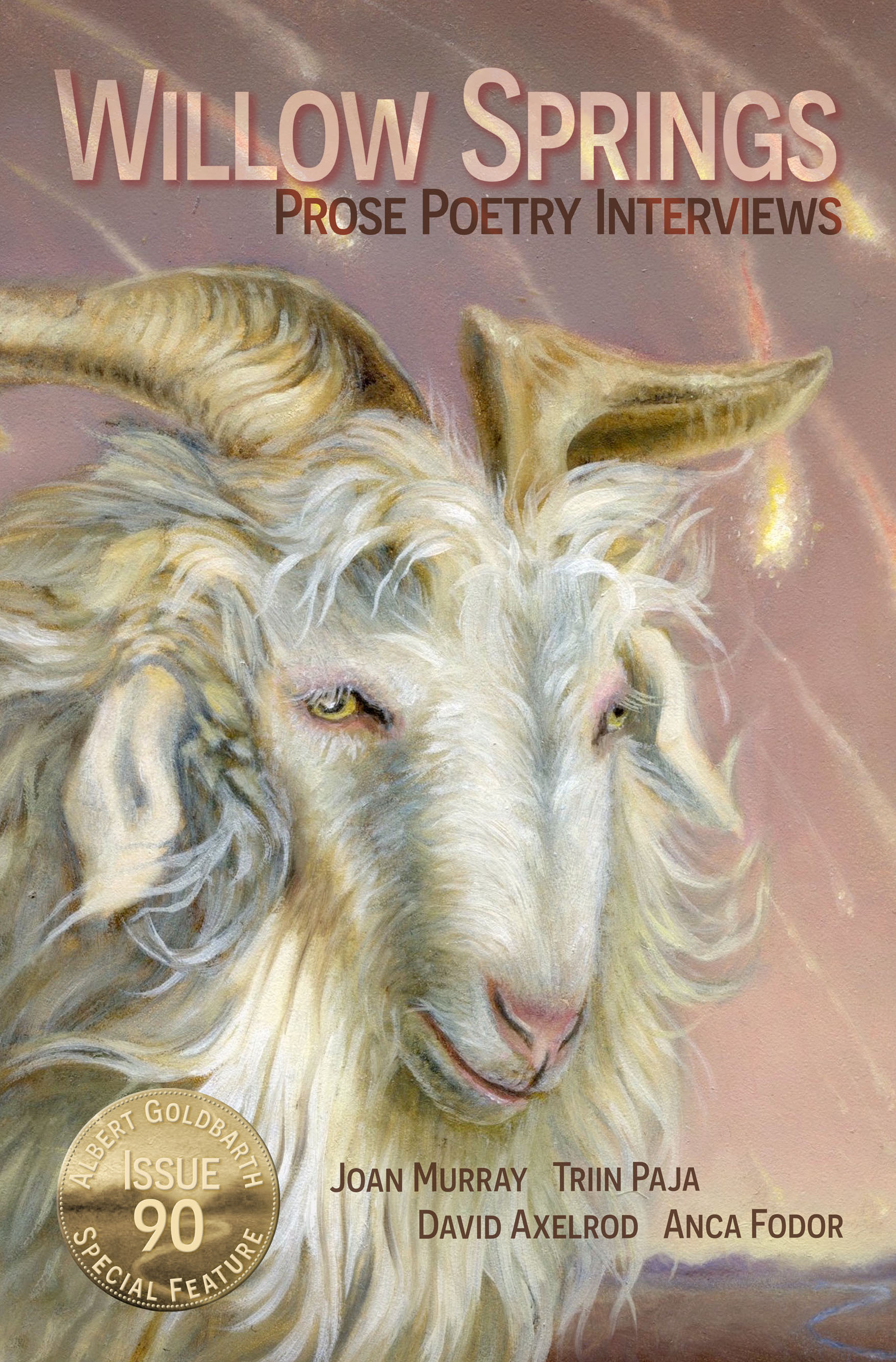

The gym is nothing like Mrs. Schafer imagined, though she has never actually been in a gym. The music is deafening when she pushes open the door. She looks around, alarmed, and sees a DJ booth to her right, where a girl, so tiny she's barely visible over the turntables, flashes Mrs. Schafer a miniscule thumbs up. Purple and pink spotlights chase each other across the floor. There is no desk, no reception area that Mrs. Schafer can see, just a number of chairs scattered around the lobby, each crafted from plastic bones to look as if you're about to sit on the lap of a human skeleton. Electric candles flicker in a huge chandelier, and plaster busts of—is that Mozart? Bach? And why would it be Mozart or Bach?—line the walls. Each has a purple plume glued behind its ear. The place has the cheap, Styrofoam feel of a haunted house. Everywhere are incredibly thin, incredibly young women dressed in black spandex.

One of these women approaches Mrs. Schafer and says something she can't hear. Mrs. Schafer points to her ear and shakes her head, but the woman just smiles, takes Mrs. Schafer's hand, and leads her through a thick velvet curtain behind the DJ booth. They walk down a flight of stairs, the woman still holding her hand, giving it encouraging little squeezes as they descend.

"Butch, this is Mrs. Schafer." The woman passes Mrs. Schafer's hand to Butch, who takes it in both of his. He is a short man, stocky, with the sort of heavily muscled arms that stick out a bit from his sides, and a long blonde ponytail that Mrs. Schafer thinks is ridiculous. "Great to meet you! Name's Butch! Ha ha!" Mrs. Schafer isn't sure what is funny exactly, unless he's laughing at the coincidence of his name. Or at her.

The gym is quieter down here, the music masked by the hum of treadmills and the clanking of weights, but there is still the odd decor, the pink and purple lighting, and now a smell, something Mrs. Schafer can't quite put her finger on. Sweat, of course, and some sort of scented industrial cleaner. Raspberry? Mrs. Schafer tries not to feel disheartened. First the complicated shoes, then the disorienting lobby, now the unexplained laughter and Butch insisting that she answer the question, "Why are you here?" even though he must know the answer. "To get in shape," she mutters, but that's not good enough. Butch makes her repeat herself, again and again, louder and louder, until she is shouting, nearly yelling in this dark, humid gym, before he corrects

her phrasing, repeating under his breath what her daughter Jessica has already told her—that no one gets in shape anymore. They get fit. It all seems unnecessarily, almost aggressively, obscure. As if the real goal here is not to help Mrs. Schafer lose forty pounds, but to strip her of her orientation in the world, to convince her that her tastes, whether aesthetic or auditory or idiomatic, should be discarded in the face of such irrefutable corporate styling.

The actual exercises are surprisingly familiar. Jumping jacks, leg lifts, attempted pushups—all stuff she did years ago in gym class, or half-heartedly on a girlfriend's living room floor. Which is fine. She doesn't need her mind blown by a cardio routine. She isn't even all that interested in getting fit— at her age, it seems faintly ridiculous, like getting a tattoo. The sessions with Butch were a gift from Jessica. A going away present, actually, because nine days ago Jessica left New York and moved some great distance. Mrs. Schafer does not know where. Jessica wouldn't tell her. She hinted that it was out of the country, someplace hot and difficult to get to, where cellular service would be spotty and the internet nonexistent.

Mrs. Schafer imagines Africa. She envisions swirls of yellow dust, bright, patterned cloth, the ribs of a lone goat. She sees Jessica—fair, flushed—pouring the last drops from a canteen onto her shriveled, white tongue.

"It'll be good for you, Mom," Jessica had said, pressing into her hand a purple gift card with the word DIESEL written across it in pink bubble script. "This guy's a monster with old lady fat. He's famous for it."

Mrs. Schafer asked but Jessica refused to provide an address, or even a phone number for where she could be reached. She said she wasn't sure yet, that her housing was still coming together, that she was suspending her cell service for the time being, because it probably wouldn't even work where she was going. She did eventually concede that she could be reached, only in the direst of emergencies, by e-mail. Though who knew when she'd be able to check it?

That was enough. Mrs.Schafer would cling to the possibility of e-mail just as she was clinging to this plastic gift card. By the time her daughter had gathered her things to leave, Mrs. Schafer had already composed in her head the thank you e-mail she would write after she visited this gym.

Jessica hugged her mother and allowed herself to be kissed, but after just a few moments she pulled back. She smoothed back her thin blonde hair, avoiding Mrs.Schafer's eyes. ''All right, Mom. See you." Mrs. Schafer had insisted she would not cry, but suddenly her shoulders were quivering and she gripped the plastic card tightly, digging it into her palms, rolling her eyes up to catch the starting tears.

"God, Mom." Jessica sighed and patted her mother once, awkwardly, on the shoulder. "It's going to be fine."

AFTER HER FIRST SESSION WITH BUTCH, Mrs. Schafer kneels down and begins pulling dusty board games and boxes of Christmas decorations from under her bed. She finally finds the scale, shoved back against the wall, but the effort of reaching it exhausts her and she lies on the cool wooden floor next to her bed, the scale balanced on her belly. Butch is no joke. Her entire body quivers like a plate of high Jell-0, the kind you set in a Bundt cake mold and stud with canned fruit. The kind no one makes anymore.

From the apartment next door comes a shriek, then another, and then a peal of happy screams. The new neighbors. Three of Mrs. Schafer's five rooms look out onto a narrow air shaft, and it's possible to see into the apartment across the way. It hasn't always been. An old woman used to live there, some sort of recluse who had papered her windows with newsprint, so that no one could see in or out. It was convenient, actually. Mrs. Schafer had never bothered with curtains in those rooms. But then the old lady must have moved or, more likely, died, because a crew came in and renovated the entire space, replacing the papered-over windows with new glass in sturdy metal frames. Now you can see into the apartment across the way, and it 's a bit startling how close it is, how if she wanted to Mrs. Schafer could lean out her bedroom window and snatch a vase off her neighbors' dining room table.

The new neighbors are a woman and child, a little boy. Most likely a single mother, or one of those long-suffering military families. And Mrs. Schafer's apartment, which for years housed its own noisy young family, now holds just a widow. It's as if the two units somehow swapped places, and one day she woke to find that the busy familial warmth she was so accustomed to had moved next door. And here she is, an old woman living alone, no doubt strange and a little sad to the young family across the way. Maybe this is how it happens. One minute you're a wife and mother, and the next an old woman living alone. Pitiable. Maybe that's how you find yourself struggling up

a stepladder to your window, a glue stick in one hand and The Village Voice in the other.

But not Mrs. Schafer. She is getting fit. She is not going to paper over her windows. She is going to install window shades. Bright curtains maybe, or those lovely wooden blinds, the tea-colored ones you see in magazine spreads of modern, Asian-inspired homes.

She sets the scale next to her and rolls to her side. Maybe she'll paint her walls. Lord knows it's been years. She takes a deep breath and heaves herself up, the room flashing dark for a moment before she steadies, exhales. Maybe a nice yellow. A nice creamy yellow with bright white trim. She undresses there in the bedroom, dropping her clothes onto the scale, then takes a shower. She forgets to weigh herself.

*

HERE'S THE THING: Jessica was not an unhappy child. If anything, she was cheerful and opinionated, sliding through the apartment in white socks, her cornsilk hair slipping from its tie, the whole skinny length of her ecstatic at biscuits for breakfast or a new plastic bracelet or her father, home from work.

And they raised her well. She could sit at a table full of adults and not fidget, answering questions in full sentences and always coming up with some anecdote about school, something endearing and short, before letting the adults get back to their talk. She was equally good with other children. She could run and shriek and make friends at the park, unlike her dour best friend Marabell, who was also an only child but raised by psychoanalysts, and as a result was always appearing solemnly in the kitchen when the girls were supposed to be making crafts, her gaze unsettlingly direct, calling Mrs. Schafer by her first name and wanting to know how long she and Harold had been married before having Jessica, or whether Mrs. Schafer was fulfilled by her work. If Mrs. Schafer had been asked to put money down on which of the two girls would cut off all ties with her mother and fly to Africa, it would have been Marabell. Obviously.

But Marabell seems perfectly adjusted. Each Christmas she sends Mrs. Schafer professionally-lit photos of her three young children, with funny, self-deprecating anecdotes written on the back. She lives in Park Slope, two blocks from her analyst parents, while Jessica sleeps in a mosquito filled hut across the world, no doubt already feverish with malaria.

Mrs. Schafer wonders when Jessica will come back. She is certain that she will. Jessica, while adventurous, is a creature of convenience, fond of delivered food and late night nail salons. Mrs. Schafer does not allow the cold oil slick of doubt to bubble up, the persistent certainty that, when Jessica returns, it will be in secret.

MRS. SCHAFER'S SECOND SESSION WITH BUTCH is much like the first. She is required to shout at the start and then jog in place, lunge and squat, sit up and pull up and push up. She is also given a lecture on posture. "Posture," Butch says, "is your way of showing the world you're ready for anything." Now, before each exercise, she is to plant her feet as wide as her hips and square her shoulders. She is to communicate with her body that she is ready to get fit.

As far as she is able to tell, Mrs. Schafer is the only person over forty who frequents this gym. Everyone else is very young and very fit, with attractive outfits and coordinating sweatbands. The women wear makeup that never smears, and the men have astounding muscles that Mrs. Schafer finds herself staring at, trying to determine how they could possibly correspond to her own largely invisible ones.

Still, people are kind. They nod at her as they pass. They let her go ahead at the water fountain. They rack her weights for her, though Butch discourages this. A young man even winks at her as she slides her free weights back into their colorfully labeled slots. She finds herself nodding back, smiling, even chatting with two young ladies in the locker room about their stylish gym bags. The decor, while still ridiculous, does not bother her so much this time. She sees in it a playfulness, a lack of seriousness, that is almost charming. She wonders if it's possible that she might like the gym.

Only Butch seems a little subdued. He still high fives and fist pumps and growls at her when she slows, but a few times when he should have been counting her reps she catches him staring at the floor, biting his lip with his short, thick arms crossed at his chest. She has to keep herself from asking what's wrong.

SHE GETS HOME from her session with Butch and lies on her bedroom floor, the wood cool against her sore body, the scale under her head like a pillow. Then someone screams. It's the family across the way and the screaming is so abrupt, and at such a desperate pitch, that Mrs. Schafer knows at once that this fight started much earlier. There was a pause maybe, a silent seething refueling just as Mrs.Schafer came home, but now things are warming up again.

"Bitch!" the boy shouts and his voice is high and girlish. "Bitch, I hate you!"

"Oh yeah?" the mother shouts back. Her voice is also high, but there's a rasp to it, as if she smokes. "You think you hate me?"

And then there are sounds of impact, books being thrown or chairs knocked over. Or maybe the boy is being beaten.

Mrs. Schafer rolls onto her hands and knees and crawls to the window. She brings the scale with her and sets it against the glass, hoping it will shield her as she peeks into the apartment across the way. Really, she should go out. There's a movie she's been meaning to see. Instead, she stares at the blank wall of what must be her neighbors' living room, half-hoping, half-dreading that the fight will move into view.

Something does move, a shadow sweeping across the wall, and the boy screams again. There is a heavy thud, a long, pleading whimper, then silence. All of a sudden there is the boy, crying, sulking, throwing his body around the living room in fury and dismay. The mother appears, a bulky brunette. She swipes at her son, but she appears to have some trouble moving, something in her hip or knee, and she is too slow to catch him. The boy begins to whimper again, backing away from her. Mrs. Schafer closes her eyes.

Harold used to send Jessica to bed without supper after some undeniable infraction. Mrs. Schafer would wait until he went out for his evening cigar and then crack open the door to Jessica's room. Are you sorry? she would whisper and Jessica would whimper, the same pitiful, animal keening she hears now. She would make a plate of leftovers and tell Jessica to hide the dish when she was done. She would sleep easily that night beside Harold, lightly, sure she was able to hear Jessica's contented breathing.

Mrs. Schafer opens her eyes. The mother is gone, but the boy is still there. He is still, quiet, his head cocked, listening. He is blonde and slight, nothing like his mother. He could be Jessica's brother. He is wearing red shorts and a blue and white striped shirt. One hand trails down to his knee. He scratches, still listening, as a rare column of sunlight winds down the air shaft and through his window, making the pale white of his knee glow.

Then he jumps, whirls, his whole body turning in the air and slamming against the living room window. The sound is tremendous, the glass shakes, and Mrs. Schafer gasps, falls back. She crawls quickly into the kitchen, then the living room, where her windows look out onto the street and she can't be seen by her neighbors. She doesn't know if the boy saw her. It's possible. It's also possible that this was all for his mother. A display. He might have had some hazy idea that by throwing himself against the window he could break through. Not to kill himself—Mrs. Schafer doubts he made it that far in his thinking, five flights down to the bottom of the air shaft—but to wrench himself from his mother in the most dramatic, most magnificent way possible. He might have been trying to fly away.

MRS. SCHAFER TAKES THE N TRAIN UPTOWN and walks west to Home Depot. The building takes up a full block, the sort of cavernous space only the most massive chain stores can afford. It's late September and already starting to get cool, but air conditioning blasts her as she pulls open the heavy glass door. She wishes for a scarf. Directly ahead is the lighting department, and past it is Kitchen, then Bathroom, then Flooring. She wanders the store, unable to find window dressings or a salesperson for an impossibly long time. After her third loop through Lighting, she is about to leave when a skinny young man asks her if she needs assistance. His nametag says José.

"I need some curtains. Or maybe some blinds. I'm not quite sure."

"Of course, ma'am. I can assist you with that. Do you have measurements?"

Measurements. Of course. This is not the first time she has redecorated. There were phases, several of them in fact, when she immersed herself in a flurry of design, carrying in her purse at all times the dimensions of her apartment down to an eighth of an inch, buying tables and art and lamps that fit just so. But today she has come to Home Depot with nothing. She shakes her head, embarrassed.

"Maybe I should come back later."

"No need, ma'am. If you'll just follow me."

José leads her to an elevator she had not noticed, and then they are upstairs, standing on some sort of narrow catwalk overlooking the store. The air is warmer up here. The separate departments—Lighting, Bathroom, Kitchen, Flooring, Garden, which from down below felt labyrinthine, as if every turn were only winding her deeper into the cold fluorescent heart of the store—are suddenly laid out on a neat grid. Home Depot salespeople in cheerful orange aprons are spaced evenly throughout. The shoppers look casual, unhurried, from this height.

Mrs. Schafer sighs, letting the air stream slowly through her nostrils. "This is amazing," she says.

"Yes," José nods. "I know."

Window blinds have been installed onto fake windows along the catwalk. Lightbulbs shine behind the blinds, simulating daylight, Mrs. Schafer supposes, or perhaps the maddening electric light that now pours from her neighbors' windows into hers far too late into the night. José leads her to each display and encourages her to pull the various cords and sticks and ergonomic levers. He explains that each set is made of all-natural, environmentally-sustainable wood—cherry, teak, bamboo, cedar—and he lets each name hang in the air for a moment, as if the very syllables of cedar imply a customer service experience of shocking quality.

José stops after the last display and turns to Mrs. Schafer, sweeping his arm to take in the catwalk, the window blind displays, the pleasantly warm air, the humming, well-ordered grid below. "This is Home Depot's Regal Windows Measurement and Installation Service, ma'am."

Mrs. Schafer nods encouragingly. What a good idea this all is—the catwalk, the private tour, the blinds installed over fake windows, the thoughtful touch of the lightbulbs.

"You work with a Home Depot Regal Windows In-House Stylist to realize your window vision. We come to your domicile and take custom measurements. We place any orders. Our skilled technicians do the final installation." José pauses, his arm still hovering in the air, as if he is considering whether or not to continue. "It's a premium service, and while it's not for every customer, for you I could not recommend it strongly enough."

Mrs. Schafer knows that José probably uses this line with everyone. But there is something in his low voice, in the way the lids of his eyes slide down and his chin tips up as he speaks, that makes her wonder if there is something a bit premium about her. Between Harold's pension and her 401(k) and the apartment, fat with equity, she does have a bit of money. And she's getting fit. Butch said it would take two to three weeks to begin seeing real results, but maybe not. Maybe it doesn't take nearly that long.

When she gets home, she's going to e-mail Jessica. Jessica loves premium services.

"Okay," she says, and she plants her feet as wide as her hips and squares her shoulders. "How do we proceed?"

MRS. SCHAFER TRIES TO BE HONEST WITH HERSELF. Particularly first thing in the morning, when she sips her coffee by the open living room window and her mind is sharp and probing, slicing back swaths of vanity, needling down to the hard nut. What could have done it? There were the times when Jessica was young and Harold said a firm No, only for Mrs. Schafer to sneak into her room a few hours later to whisper Yes. There were adolescent difficulties—the normal struggles over authority, the

punishments that were perhaps too zealous. There was Harold dying much too young, when Jessica was only seventeen. There were Jessica's unfortunate boyfriends and cigarette butts in the toilet and the discovery of a little baggie of cocaine that was probably too much of a shock to Mrs. Schafer. She had probably overreacted.

But after Jessica moved into an apartment of her own, their relationship had entered a peaceful phase, or so Mrs. Schafer thought.

For years now there have been weekly phone calls and dinners three times a month and quiet, lovely holidays.

She is not a perfect parent. She would never claim to be. But even on these honest, brutal mornings, Mrs. Schafer cannot find a reason. None of it seems like a good enough reason.

Unless.

On this particular morning, one hour before her third session with Butch, sitting in the chill by the open window with her coffee mug warm in her hands, Mrs. Schafer remembers something. It is something small, something practically insignificant, but as it rises up—as the batting of time falls away and it is there before her, purple and somewhat tender, like a bruise—she thinks, Unless.

Some twenty-five years ago, while Harold was away on a union retreat, Jessica had a nightmare. It was one of those stifling August nights and they didn't have air conditioning at the time, just a loud metal fan they dragged from room to room. Mrs. Schafer lay on top of her sheets in only her underwear. Jessica was just six and had not yet developed the shrieking disgust, the aggressive adolescent shame that would later bully Mrs. Schafer into buying pajamas. On hot nights Mrs. Schafer was still free to sleep naked, or nearly so, not even bothering with a robe when she padded to the bathroom.

Mrs. Schafer didn't hear Jessica come in, just woke with a start to see her daughter standing by the bed, her face shiny with snot in the dim light. She was so small, even for six. Practically still a baby.

"I was in the hair nest," Jessica said.

Mrs. Schafer rolled to Harold's side of the bed and patted the damp sheet. "Oh dear. Were you all alone again?"

Jessica had been having this nightmare for a few weeks now. Her bed would dissolve beneath her so that she plummeted into a huge, awful nest of human hair. This worried Mrs. Schafer, but Harold dismissed these nightmares as par for the course. Life is full of horrible shit, he said. If all that cluttered the darkest corners of their daughter's mind was a hair nest, they were doing all right.

"No," Jessica said, climbing into the bed. "There were baby birds in there with me."

"Well, that's nice."

"No, it was not nice. They were mad at me. They pecked my head."

"Mean ol' birds." Mrs. Schafer pulled her daughter close and pressed her nose into that thin, sweet hair. "They should know better."

Jessica sighed and scooted closer to her mother, nuzzling her wet face against Mrs. Schafer's breasts. Mrs. Schafer shifted slightly, trying to give her daughter more room, but Jessica followed her, rubbing first her cheek, then her mouth, against her mother 's nipple. And then she began to suck.

Years later, alone in her living room, Mrs. Schafer is able to explain it. Jessica was vulnerable, she was scared, and so she had regressed back to her babyhood, back to when her mother's body was the source of all comfort. And Mrs. Schafer had been half asleep herself. Had she been awake, had it not been three in the morning, had there not been a full day of work behind her—nine hours processing billing at the hospital and then to the babysitter's to pick up Jessica, to the store because there was nothing in the fridge, dinner cooked and served and cleaned up, lunch packed and homework checked and bath and story and bed, all by herself this week with Harold gone, and tomorrow just a few hours away, tomorrow when she would somehow do it all over again—it never would have happened. She would have stopped it. A gentle correction. A defining of boundaries. A distinction made between baby Jessica and big-girl Jessica. She would have stood up, put on one of Harold's oversized shirts, and carried Jessica back to her own bed.

But instead she let her daughter nurse at her dry nipple. She did not think of repercussions, how they might stretch decades into the future, how this unexpected intimacy might create a tiny ripple in their relationship, how such a ripple could amplify over the years into great, shuddering waves—Jessica pressing the gym gift certificate into her hand, wrinkling her nose as she said old lady fat; Jessica hugging her awkwardly, at a distance, refusing to let her chest press against her mother's; Jessica

gone, vanished, having ruthlessly, almost gleefully shed her old life, the one that included Mrs. Schafer.

It had felt good. And so what? Could she be blamed, should she be punished, for feeling as she drifted to sleep that her daughter's mouth on her breast was still a mouth, her daughter's body hot against hers still a body? Wires had been crossed in those moments. She had arched sleepily, murmured, and as she passed over she did so with the languid, purring pleasure of a woman whose body has been used.

It was not her fault, Mrs. Schafer thinks. She did nothing wrong. And Jessica was fine. That night she fell asleep, Mrs. Schafer's nipple sliding from her mouth, and the next morning she woke cheerful and well rested, excited about the birthday cupcakes a classmate was bringing to school, seemingly oblivious to her mother's sneaking glances. They never spoke of it. Mrs. Schafer never told Harold what happened. It is likely Jessica doesn't even remember. It is likely that night had nothing to do with what was to come.

Mrs. Schafer's coffee has gone cold. She reaches to set it on the windowsill, but the ledge is taken up with her scale. She put it there yesterday, to get it out of the way while she swept. She sets her mug on top of it, watching its thin red arm shudder before settling back on zero.

DURING HER THIRD SESSION WITH BUTCH, Mrs. Schafer is stepping on and off a knee-high orange box, feeling somewhat like a circus animal, when Butch asks, "So, how's Jessica liking Tucson?"

Aha! It is obvious from Butch's tone that he is trying to be casual, but then he clears his throat, coughs into his fist, pats his chest as if he's coming down with something. Mrs. Schafer had assumed that Jessica found Butch on the internet, or saw an ad on the subway—Butch: A Monster with Old Lady Fat!—and jotted down the number. But now it's clear that Jessica knew Butch personally. Maybe she had trained with him? Or-could it be possible that they dated? Could Jessica find such a man attractive? Jessica, who may not have been beautiful but was tall and slim and young, all of which seemed to pass for beauty these days.

It is only then, trying to picture Butch and Jessica together, walking arm in arm, the top of his head reaching only her shoulder, that the full meaning of Butch's question hits her. How's Jessica liking Tucson. Tucson . Not Africa. Not Antarctica. Arizona. They surely have cell reception in Tucson. They definitely have the internet.

Mrs. Schafer plants her huge right shoe on the orange box and steps up. What could possibly be in Tucson? A job? A man? A cult? She brings her knee to her chest, then steps down off the box. No. If there was something to know, Mrs. Schafer would've known it. She knows all about her daughter's life—her friends, her dates, her triumphs and blunders, the trends of her interests, her flirtation with veganism, the awful four months she recited poetry at spoken word readings.

Mrs. Schafer steps back onto the box, this time with her left foot. Her heart is pounding and sweat slides down her forehead and into her eyes. If there were somebody or something in Tucson, Mrs. Schafer would have had some hint. She would have known.

"Keep it movin'!" Butch growls. Mrs. Schafer is standing on the box, breathing hard through her mouth and blinking, trying to clear the sweat from her eyes. She brings her right knee to her chest and then steps down off the box.

She wants to squeeze Jessica. She wants to take her by her narrow shoulders and squeeze and squeeze until her silly elusive entitled daughter pops like a bag of chips. Deflates. The air hissing out of her until all that's left is skin, a pelt, a long golden flag Mrs. Schafer will fly from her window as a warning.

She plants her right foot on the box and uses the sleeve of her T-shirt to wipe her face. Her skin is hot, unbelievably so, and blood pounds in her temples. She tries to heave herself up, but she has misjudged the edge of the box. She wobbles, swinging her arms, as a high animal yipping escapes from inside her. Butch reaches for her but is too late. Mrs. Schafer falls, her ankle rolling beneath her, her wide, soft body with its copious fat hitting the blue mat with a tremendous sound, a loud, echoing slap that reaches the dim corners of the gym.

"Jessica's fine," Mrs. Schafer says. She is gasping, she can barely breathe. She is lying on her back squinting up into the purple lights. "Having quite an adventure, I imagine."

THAT AFTERNOON, MRS. SCHAFER WEIGHS HERSELF for the first time. She

knows she was supposed to do this before she started exercising—Butch was adamant about establishing a "base weight"—but she has avoided it until now.

She carries the scale to the bathroom, hugging it to her chest so that the red arm climbs and climbs. She's able to get it to one hundred just by squeezing. She sets the scale down carefully, on the flattest part of her crooked tile floor, and turns on the shower. She removes her clothes and faces the scale, her feet as wide as her hips, her shoulders squared, and then steps on.

Two-hundred-and-seven.

She steps off, then back on.

Two-hundred-and-seven. The arm quivers with her weight. She tests it, bouncing a little, watching it swing up to two-fifty-two, then down to one-eighty, then settle back on two-hundred-and-seven.

She knows this number is high, though she's not sure how high. She doesn't know what her weight should be, what would be considered healthy for her height and age, what would alarm a doctor. She waits, for shame, for disgust, for any emotional

recognition of all this old lady fat weighed out in front of her. But nothing comes. If anything, she is relieved. Two-hundred-and-seven, a nice number. The warm, round two and oh, the handsome slash of the seven. A number that seems affectionate somehow. Accepting.

The shower is heating up, the air around her growing warm and moist. Jessica, of course, would not find two-hundred-and-seven acceptable. If anything, it would make her angry. That Mrs. Schafer weighs this much to begin with, that Mrs. Schafer does not care. That, by the cruel logic of genetics, Jessica herself could weigh two-hundred-and-seven someday.

Mrs.Schafer begins to bounce again, harder this time, trying to swing the arm up to three hundred. She can feel her flesh quivering, the mottled landscape of her thighs, the heavy knocking of her breasts. Steam drifts from the shower, slicking her skin. She lifts her hands and waves them, setting the hammocks beneath her arms swinging. Two-oh-seven! Here it is! All of it shaking! All of it ready!

"Hey!"

Mrs. Schafer freezes.

"I see you!"

The voice is coming from behind her. She turns, slowly, and bends to look through the narrow crack that is her bathroom window. The glass is frosted, though she's propped the bottom portion open with a screen, now thick with dust. She would never have thought anyone could see into her bathroom. But there, across the way, are the unmistakable blue eyes of a little boy, peering out of his bathroom window. As soon as she sees him he ducks, and she can hear the muffled laughter, the ecstatic withheld giggles of a child.

She ducks too and sits on the lid of the toilet. It's wet from the steam and feels incongruous, even a little illicit, against her bare bottom. She wonders if the boy did indeed see her on the day of the fight, if her gawking has invited this attention.

She also wonders what sort of impression she will make on this boy. She doesn't know if kids these days have any idea what women's bodies look like—real bodies—or if their only references are billboards and magazines. Is he thunderstruck by the pull and roll and flap of her? The fat? Is this the firm planting of a lifelong disgust? Maybe not. Maybe he's still too young. Maybe all he knows is his mother's body. Maybe Mrs. Schafer, all two-hundred-and-seven pounds of her, is appealing in her novelty. Erotic. Maybe she will be the somewhat questionable seed of the boy's first masturbatory experience.

She is surprised to discover she doesn't care either way. Disgust or appeal, aversion or allure. Or even nothing at all. Even the flat blue-gray of indifference. Either way a Horne Depot Regal Windows In-House Stylist is corning on Monday to measure her windows. Either way she is getting fit. She has booked a regular appointment with Butch for every Tuesday afternoon, even after her gift card has run out.

Mrs. Schafer stands, plants her feet as wide as her hips, squares her shoulders, and cups her long, flat breasts in her palms. She offers them to the boy, holding them up and out like a tray of sandwiches. The steam from the shower curls around her. She does not look to see the expression on the boy's face. She does not look to see if he is even still there, if her silence has drawn him out, or if he is like an exotic animal stumbled upon, frozen, a gasp away from bolting.