Found in Willow Springs 53

October 24, 2003

Brian O’Grady and Rob Sumner

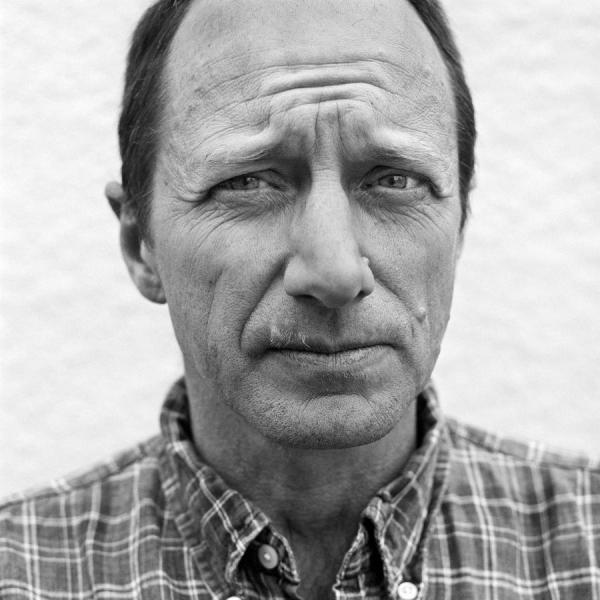

A CONVERSATION WITH RICK BASS

Photo Credit: The Elliot Bay Book Company

RICK BASS IS THE AUTHOR OF EIGHTEEN BOOKS of fiction and nonfiction, including the novel Where The Sea Used To Be, and editor of the anthology The Roadless Yaak. Bass lives with his family in northwest Montana’s million-acre Yaak Valley, where there is still not a single acre of designated wilderness. In October 2003, Rick Bass talked with Brian O’Grady and Rob Sumner at the home of the writer John Keeble, a ranch located southwest of Spokane, Washington. During the conversation they sat on the rear porch, still under construction, and enjoyed a meal of freshly slaughtered pork as the sun settled into the horizon beyond the hills of pine. We are eating bowls of chili.

BRIAN O’GRADY

Before you started writing, what effect did a compelling story have on you?

BASS

Before I started writing, I read a lot, as a child, but certainly not as much as my children read, it’s just what I thought of as a lot. And I’ve met other people along the way who really do read a lot, what I’ve thought was a lot was more just a hobby. I’m in awe and some envy of truly serious readers. That’s a long answer to say I probably didn’t read as much as I thought I did. I loved it and I read everything I could but there’s people who don’t go to sleep because they love reading, I mean they read twenty-four hours a day. In retrospect I realize I’m not one of those kind of people and certainly now that I’ve become a writer I don’t have the luxury or indulgence of becoming that kind of person when paradoxically I most need to be.

A single story can have a huge influence on a writer, or a reader, or any person, and for me that story was Legends of the Fall, the novella by Jim Harrison that really made me want to write fiction. I loved to read fiction, I loved to read nonfiction before that point, but reading that story made me want to try and write it. I don’t why. I mean I know why I like that story, why I love that story, but I just remember having that impression of how big—the cliché about that story is epic, which is an overused word, but I just remember how big the emotions and content, scale, voice, everything about that story was larger and fuller than what I had read previously. And not to take away anything from Legends of the Fall, I’m not saying it’s the only book that way. It could have been other stories in the world but I had not to that point read them. I believe there’s a story like that for every reader. I think eventually, sooner or later, you encounter them. If they make you want to be a writer or not, who knows? There are too many variables there, but for me it did make me want to be a fiction writer.

O’GRADY

Do you aim for that range of emotion?

BASS

No. I wish it were that simple, that I could have a guidepost, or model, or scale against which to measure each work, if that’s what you’re asking, but I don’t aim for anything other than just to do the best I can. And that almost sounds defensive, but it’s liberating is what it is. And conversely or paradoxically it’s not so liberating, because that’s pretty tough to ask of yourself to do the best you can every time. I mean you can only do the best you can one time, and then that’s your best. The only thing I aim for is to do the best I can given any emotion, any range of emotions, any character, any range of characters, any setting. Whatever story or essay I find myself in I just try to do my best, which is usually task enough. That can be taken the wrong way when I say that’s task enough. I don’t mean that, “Oh I’m so wonderful that it’s hard to match my best,” I mean it’s so easy to be lazy, I think it’s hard enough for everybody to do their best every time they go out(,) or even try to have the courage to attempt their best.

Jonathan Johnson comes out with a plate of ham, baked beans, and salad for each of us. His three-year-old daughter, Anya, and John Keeble’s dog, Ricky, come out with him.

Jonathan: I don’t think we’re going to have room for all of them here.

Rick: This is incredible. This is so good.

Jonathan: I’m sorry the silverware has to be inside the toilet paper.

Anya stays outside with us for several minutes while her dad brings out the rest of the food. Rick gives Ricky some pets.

Brian: You were right about getting out here.

Rick: Good.

O’GRADY

Do you still get the same impact that you did before your writing, when you read fiction today?

BASS

More so. Much more so.

Rick smiles.

Rick: That dog.

Jonathan: I’ll bring Ricky inside. Come on, Ricky. Come on!

Ricky falls to the deck. He wiggles about on his back and wags his tail.

Rick begins to talk but starts laughing at Ricky.

Rick: I have not fed that dog. Laughter.

Rick: Oh my gosh, you are a trickster. That’s great. No, I said, come on, not lie down and roll over. You misheard me. Roll over so I can scratch your belly and feed you. Give you pork.

Laughter.

BASS

A great story affects me more now than it ever has. I rely upon reading as tonic more than I ever have. I think that’s probably just a function of age as much as profession. You’ve seen, approaching or in the shadows of middle age, and you still haven’t seen everything but I’ve seen a lot more than I had seen when I started out being a writer, which is to say when I started out making notes about what the world looks like. That’s a bad place to come to as a person. So I really rely on fiction and nonfiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry to pull me out of that, the natural tendency we have as individuals to go into that telescopic place of diminished perception, observation, newness, wonder, all those significant artistic notions. A good story means more to me now than it ever did as a young person. Also, having wrestled with writing for almost twenty years I have a greater appreciation now for when it’s done well than I did. And that’s not to say I took it for granted when

I was younger, I still loved reading great things but my palate was not as developed then.

Rick eats between questions.

Rob: I’ll let you chew.

ROB SUMNER

You’ve noted the importance of not overly controlling your writing. When you’re developing a story how do you refrain from interfering too much?

BASS

I would say something like that and it’s true, but you grow and prob- ably contract too, but you grow as a writer, hopefully, and go through phases and spells, play to your strengths and then work on your weaknesses. For me, personally, that has probably at one time been a strength, to not control a story or just go with the intuitive and subconscious and trust those instincts and focus on feeling them as powerfully as possible. It’s hard to argue against that approach, that can be kind of a tiring way to go through stories, one after another, but it can also be deeply and strongly felt. As I get older, for lack of a more precise term, the intellectual side of writing does interest me more, if only that I’m slowly learning my way into it. It becomes like a game to try and control a story now and tinker with it, make it go this way and go that way. That’s still a dangerous impulse, and the best stories for me as a reader or a writer, and the truest stories, are the ones in which I don’t control them, but am tapped into the emotion more than the intellect. That said, I’m becoming comfortable enough with, I guess, theory, for lack of a better word, to be aware of it as I work. Structure, or any of those conscious things, as opposed to the infinitely more powerful subconscious.

SUMNER

You’ve stated that emotional truth informs the structures of your stories. Is emotion always central for you?

BASS

Yeah. To answer your second question, or to answer the question, yes, I mean if you—yes, there’s just no other answer but yes. But I’m not sure I understood the first thing you asked.

SUMNER

Well you’ve talked—

BASS

Or mentioned.

SUMNER

—about how emotional truth, that the emotion of the story that you’re writing develops the structure, kind of tells you where to go with it.

BASS

It can and usually does, and in the past it has for me, but what I’m interested in now, and maybe it’s almost out of boredom or something, but I don’t think that necessarily has to be true. You can have an emotional truth underlying a structural instability or a structural falsity, and a story could in theory be all the more powerful for that. It could enhance that emotional truth, but on the other hand to have a structurally sound and logical creation that has a false emotion, artificial emotion beneath a structure that might fit an emotion you’re trying to get, that wouldn’t work. So the answer to your question, yes yes yes, but again the obverse is not necessarily true. As long as the emotional truth is being felt by the narrator or the author you can have a good structure or a bad structure and you’re still going to have a story.

O’GRADY

Just before we sat down we were talking about your essay in Why I Write, “Why the Daily Writing of Fiction Matters.” In it you stress the importance of engagement with the world as well as with the world of the imagination in fiction. Is that balance between engagement and imagination an evolving process for you?

BASS

I want to say no, I want to say that it’s pretty much a fixed variable, a fixed rate, a constant, that I need a certain amount of x to yield a certain amount of y, and that’s what I believe. I don’t ever write about that. You would think—I would feel like that can’t be possibly true, because people change, everything changes in the course of its existence, but it seems constant to me. When I get enough physical activity, that yields intellectual and emotional growth for me or even an expansion of feeling. And when I’m not in the physical world the other aspects of me tend to shut down too. It’s just that simple. That’s all.

O’GRADY

Along those lines, something else that you mentioned in that same essay, have you been able to follow the advice you give, to be able to write every day and also to be in constant contact with the physical world in light of the other activities that you do?

BASS

That’s a trick question. Let me figure out how to get there. For the benefit of our reader, can you clarify that device of which you speak, of which we speak?

O’GRADY

In the essay you say specifically that you spend your mornings writing and then your afternoons walking.

BASS

Oh, yeah, yeah. No, because sometimes I tell stu—I thought you were talking about another advice, a device, so, good, you’re not, because I don’t follow that one, that other one. But I don’t follow this one either anymore. [With] the activism and family desires and obligations, I just make a choice every day. I’ve got to do what I want to do after writing and some days I don’t even write because of the other obligations of activism and so on. So no, I don’t, and that’s a real handicap. But everybody has handicaps. Some people have to work for a living. [laughter]

SUMNER

You’ve warned of our culture’s increasing corporatization and homogenization and how writing is a way to rage against the resulting constriction and entrapment. How does writing challenge sameness?

BASS

How does writing challenge what?

SUMNER

Sameness.

BASS

Well within writing, back to that notion I talked about [earlier], about literature being about loss or the recognition of loss, you’re also remaking the world. Either you’re celebrating the world the way it is, knowing that it’s not going to last that way, or you’re already actively re-creating an alternative world, an alternative logic, an alternative justice, alternative boundaries in the world. You’re putting on paper and presenting to the ‘true world’ or the ‘real world,’ the existing world or the present world. And that very act challenges sameness. You know, you’re putting your money where your mouth is, you’re investing the time of your life to put down this model, this blueprint, this plan of another world with other values, and giving craft time and attention to that work, just as surely—

Rick is interrupted by Jonathan Johnson, who comes outside with three beers.

Rick: Oh, I can’t, I wish I could!

Jonathan: You’ve been bested, eh? [laughter]

BASS

Writing doesn’t necessarily have to challenge sameness, I mean you could be a press flack for the Bush administration and just be fighting furiously to hold on to the status quo and pull the wool over voters’ eyes and say all is well in Bethlehem. So writing doesn’t necessarily have to challenge sameness, but, on the converse, it certainly can.

SUMNER

You’ve quoted before William Kittredge: “As we destroy what is natural we eat ourselves alive.” That’s quite different than what Bush’s press agents are writing. Your own writing seems to tend to something quite different than a Bush press agent.

BASS

I mean fiction, good fiction, has that quality of naturalness to it, in that it’s being its own thing, and you don’t even know what that thing is, you just know you have an emotion, you don’t know what story is going to come out of an emotion, you’re not trying to advance an agenda, you’re just trying to get an emotion out of the vessel of your body into the world, and that’s the only agenda at play in good fiction. That’s a pretty natural process, it’s an expulsion, and a procreation or a creation or perhaps a re-creation of an emotion in you, but it’s creative. So that is natural, it’s not a destructive or even really manipulative impulse, or exploitive. It’s pretty natural.

Nonfiction, on the other hand, can be a real challenge. You can have other less primary, less elemental goals or desires in the writing of nonfiction. You can have direct values that, by the nature of the medium, come into play. It doesn’t mean it’s less natural, and for that matter to say that to manipulate or exploit is unnatural is like a dog chasing its tail. That’s natural too but I don’t think of it as being as primary or elemental—that’s the raw emotion with the human filter. What I like to think of as really good fiction I think of as being more primal than that, not even having the human filter but just being the thing itself: the physical essence of joy or sorrow rather than the narrator or writer filtering that emotion into creative nonfiction.

SUMNER

In a book like Oil Notes you paint a picture without trying to change anyone’s mind. In other nonfiction books, like The Nine Mile Wolves, you’re trying to affect change. And then there’s your fiction, where you don’t know what’s going to happen.

BASS

That’s a fair gradation. For me there’s pure fiction, and then creative nonfiction which just has kind of an edge of me or the human condition. And then there’s the you-know-what-you-want-and-you’re-going-after- it kind of nonfiction which is more of the latter group, The Nine Mile Wolves or The Book of Yaak kind of book.

SUMNER

So are these different types of writing definitely separate for you?

BASS

It’s almost a question of level, how far into the subconscious I am. With fiction it’s not even a temptation to bring in an agenda or even me. You’re supposed to be in the characters and in the setting and that means you’re not in you, that means you’re certainly not in your politics. And in environmental advocacy work you’re so into the issue your art doesn’t get into it at all. I guess the creative nonfiction part of that triumvirate is where it can get interesting, where you can bring in some pure fiction for a while and then also attempt to bring in some hard core advocacy. That can be interesting. But that’s why it’s the middle ground for me. With fiction I’m not ever even tempted to get on a soapbox.

O’GRADY

You said before that writing and reading fiction can help writers and readers overcome natural and cultural boundaries.

BASS

I suppose it can. I don’t remember saying that.

O’GRADY

I’m paraphrasing of course. Do you think that as a country we look at fiction in that way, as a weapon against those tendencies?

BASS

I’ve never thought about it. Are you asking me how I think in this country we tend to look at fiction? This is going to be off the kettle, calling the stove black or however that saying goes, but I think in this country. There’s a tendency among too many to look at fiction as making a statement of politics or even personal values. I understand what a joke for [it is] me to say something like that, because my environmental advocacy is so fiercely partisan. It depends on the reader but I see a lot of people read fiction and try to filter it through a lens other than what I think the writer was intending, which was the human condition. A lot of readers will try to extrapolate from a piece of fiction into judgments and assumptions that don’t hold up. But it’s always been that way, and that’s a weakness but it can also be a strength of fiction, the fact that it can be mutable, that it’s a universal currency, that it can be a universal dialect in language. It should be, and yet the readings of so many books are slanted toward the times, the culture, this day and age. It’s a good question but I can’t answer it. Most readers are different.

SUMNER

If we could talk about your new collection The Hermit’s Story. Longing has played an important role in your fiction. Earlier work has often focused upon the rage of people as they try to get along in an uncooperative world. In the new collection we find characters such as Dave in “The Prisoners” and Kirby in “The Fireman,” divorced men who can see their daughters only rarely. Both Dave and Kirby have moved from rage towards a more deadened feeling. What interests you in their saddened, hardened emotional state?

BASS

I don’t know, I don’t know. What you said previously, about them moving toward detachment, may be what touches me about characters in those situations, that they’re moved toward survival and their acceptance of pain. Under one reading you could look at characters in those stories and say, “Well, they’re copping out, they’re detaching rather than embracing their pain,” but I don’t read those, or I don’t read “The Fireman” that way. [In] “The Prisoners” the characters have more of a subconscious detachment, they haven’t yet realized that they’re detaching to stay alive, but if you’re trying to stay alive then you’re trying to avoid foreclosing on the possibility of not being able to be sensate. So that is, if not heroic, it is still nonetheless, well it’s maybe not even dying but it’s not a full disengagement. You can detach in order to retain the ability to engage, and I mean that’s what, it’s just a diminution of ambitions, perhaps. Bittersweet would be the emotion there. And that’s an interesting conflict or interesting tension, interesting duality of emotions…[trails off]

Jonathan Johnson is approaching the table with three pies balanced on his arms.

Rick: Good god almighty!

Jonathan: One per each. Pumpkin cheesecake, turtle cheesecake, and pumpkin pie.

Brian: Umm, I’ll have some of the pumpkin pie. Rob: I’ll try that pumpkin cheesecake.

Rick: Ah…My God, that’s the hardest question. Johnson: He’s been rendered inarticulate by dessert. Rick: Yes, yes, all of it.

Johnson: All of the above, eh? Rick: Just the tiniest sliver.

Johnson: Of which? Rick: Of yes, of each. Johnson: Okay. I gotcha.

Rick: I mean, but you can imagine…pie.

Johnson: Pumpkin pie, pumpkin cheesecake, tiny sliver of each. Can somebody open the door?

Rick: Yes.

Rob: No more sun.

Rick: Yeah, never was much. Frosty. [eating] What are these little red things?

Brian: Those are pomegranate seeds.

Rick: Oh yeah?

Rob: Yeah, they were good.

SUMNER

Kind of tied into the longing, what we’ve just been talking about, memory in your work seems to work as a type of longing. Ann in “The Hermit’s Story” holds a memory of her trip to Canada “as tightly, and securely, as one might clench some bright small gem,” and Russell and Sissy in “The Cave” are hit by the realization that though their memory of the cave was bright and strong in that moment, “even an afternoon such as that one could become dust.” These are characters trying to hold on to what has already passed. In a way they reflect your stressing of fiction as a way of reconnecting what has been isolated.

BASS

Not to sound like a smart ass, but yes. I mean, I would agree. Certainly. I’m not conscious of those kinds of thoughts but that doesn’t make them any less true or even surprising to me that I wouldn’t have been able to explain them. A lot of people talk about memory as a kind of landscape, and that really interests me, that makes sense that, you know, you’re looking back, but . . .

Jennifer Davis comes outside with plates of pie. Jennifer: . . . cheesecake. [laughing] Sir.

Rob: Thank you. Brian: Thank you.

Jennifer: Here you go. [To Bass:] Yours is coming. Rob: Yours takes more time.

Rick: Bring the wheelbarrow!

BASS

But, in memory, you are obviously looking back at country that you traveled through, you are making a map, a map of that territory, but the way you say it was smarter. […] I mean, fiction is a device to preserve memory? Is that what you meant? Enrich memory?

SUMNER

To try to hold on to our own memories, or things that we’ve lost.

BASS

Hm. I suppose so. I mean again, literature is about loss or the recognition of loss, in celebrating or bringing the attention of art and craft to a story you are both celebrating and preserving something, for sure. You don’t think about presenting it to a future, but I think about presenting a story to the present, because it’s already in the past as you imagined it. There’s some movement across time and it’s almost kind of a resurrection, sure. Take something from the past and bring it all the way back up to the present, take it back to the contemporary moment, and that is an act of preservation.

My own memory is really bad, so I suspect that there’s something larger to that than what I’m grasping.

Rick: You guys are missing out. Rob: The turtle?

Rick: Yeah.

Rob: Yeah, I was eyeing that one. Pumpkin cheesecake. Maybe there will be some left for us when we’re done.

SUMNER

Now here’s another. Let’s talk about work. Artie in “The Prisoners” works in real estate and Kirby in “The Fireman” is a computer programmer. Both men find their jobs either numbing or irrelevant. They make money for their companies but find very little value in their work. So Artie goes fishing and Kirby volunteers as a firefighter, activities that working-class people do for a living. In the fishing and the firefighting there is an immediacy to the activities, a direct physical engagement with the world around them. What’s the relationship of work and passion in these stories and in your writing?

BASS

I don’t know. I don’t even know how to explain it, but work is what you do, that’s how you are—one of the ways—that you are in the world, to state the obvious, and almost everybody has to work. If you’re going to write a story about engagement with the world . . . Let me back up. I guess what it speaks to in part is what kind of story do you like as a reader and a writer, and the stories of the sad, dead weight, heart-dead, bittersweet, life-wasted stories of detachment and desensitization that are not infrequent in contemporary literature, while technically masterful and even emotionally masterful, after a while I get to feel, as a reader, cheated by the repetition of these subdued responses when the point of the story is your response to it. A little goes a long way, I get it! And that’s life, I get it! And so I like to personally look around for almost more elemental stories, where there’s a little less ambiguity. I don’t think that gives up anything in terms of sophistry, I don’t concede that at all in stories that really speak to me. If you’re interested in reading or writing a story about which a partly successful attempt at greater engagement with the world is achieved, it’s hard, a real trick to pull that off with a story about somebody who didn’t do something, as opposed to a story in which it was in somebody’s character to do something, and work is something to do, so it seemed hard to leave work out of some stories. But the wind is in your face if you’re going to write a story about somebody who’s going to feel the world deeply, but that person doesn’t feel deeply enough about the world to engage with it except when he or she is on the pages of your story. It seems artsy—it can run the risk of becoming artsy and artificial. There are, I’m sure, people who do not work who are fully engaged with their senses and the world, but the wind is in your face, in the writer’s face.

Rick coughs.

Rob: You doing all right?

Rick: I’m shoving pumpkin pie in my face. I’m doing all right. [pause] It’s my favorite.

O’GRADY

In “The Distance,” you have a Montana family visiting Monticello with the result that Thomas Jefferson, westward expansion, and the dynamics of one 21st-century family coalesce into a single story. Central to the story is the boundary between wilderness, or wildness, and control and our attempts to balance these elements. What motivated you to dig into the mistakes of America’s past?

BASS

Um, almost sounds like a smart-aleck answer, but—

O’GRADY

If you take issue with the question—

BASS

Well, not even so much as issue but again a lot of the questions you’re asking are so thoughtful, intelligent, that there’s a danger of them presuming an awareness on my part that that’s what I was aiming at, which was not the case. It doesn’t make it not true, I just didn’t know of some of the things that were going on there. The arc of this country at this point in time I find severely disappointing, and there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t fret about or rage about it. So that’s embedded in my subconscious, it’s embedded in my subconscious that it even comes up into my consciousness, but I don’t set out to write fiction to say those things. I just think, “What am I feeling?”, and then I start painting pictures and say, “This is what I’m feeling. This is what I see.”

So I would not argue with any of that, but it was not a conscious goal, because that would be a political assertion. It’s there, you’re right, but my first impulse was just trying to get the pictures accurate, that landscape, that point in time, that disparity between them. The Louisiana Purchase inhabitant in new-time versus the Louisiana Purchaser in old-time and the crisscrossing, it’s just a good structure, a good zone, good opportunity for conflict and richness.

Something about that story . . . Well, you asked, “What, what was the genesis for that dynamic?” I think what authorized me to tell a story like that, or enabled me to, is that living in the Yaak in the 21st century, we’re faced with the same choices on such a heartbreakingly smaller scale. The scale to Jefferson’s perception, then, was infinite. It wasn’t infinite, but he perceived it to be infinite, his culture perceived it to be infinite. And now, goddamn it, nobody perceives it to be infinite, we all understand how damned finite it is, we can measure down to the last foot how finite it is. There is 188,000 acres of roadless lands left in a million-acre landmass in the Yaak that’s still even eligible for wilderness designation, which is to say let these last 18.8 percent of the landmass go about its own natural processes, to burn or rot, grow old or die, grow young again at its own pace outside of our own manipulations. Not to cast value judgments even on our manipulations, just to say these last 18.8 percent of places in this incredibly wild valley we’re going to save, for no other reason than as a test case, scientific base of data, against which to measure our own future successes and failures. So living there is where that story came from about slavery and control, land and control and science and knowing everything or thinking you know everything. But I don’t think those things when I’m writing a story, I’m just realizing it now.

SUMNER

How’s the Yaak doing, Rick?

BASS

It’s in a tough way. It’s got a Republican White House, Republican Senate, Republican House of Representatives and they’ve had three years to stuff agencies and cabinets and committees with industry lobbyists and right-wing philosophers, and they’re not big fans of wilderness or wildness. They’re not big fans of much of anything of what I care for, so it’s about the worst I’ve ever seen it. We’re in the middle of a forest- planning initiative, so if I can make a request for people who read the interview to write letters I’ll send information on that.

SUMNER

That was our last question. Do you have a final thought?

BASS

Too many final thoughts.

SUMNER

They’re never final?

BASS

They’re all final.