Found in Willow Springs 74

March 9, 2013

Elizabeth Kemper French and Joseph Salvatore

A CONVERSATION WITH ANDRE DUBUS

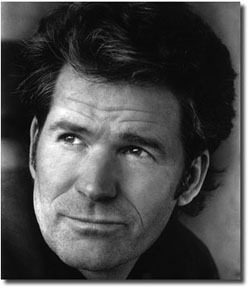

Photo Credit: andredubus.com

Andre Dubus’s fiction dives into the underbelly and wrestles with copies we often turn away from: crime, poverty, infidelity, violence, merciless bullying, and pathetic sex. His lush layers sensory detail ground the reader in the smallest moments of his characters’ lives and their often unresolved conflicts. We tumble along with them, with rarely a redemptive branch to grab on to. From his first book of gritty stories, to his novels, memoir, and most recent collection of novellas, Dubus looks unflinchingly at the inner lives of the common man and woman: bartenders and recovering alcoholics, construction workers and criminals, bank tellers and strippers, wives and husbands. Even though these characters are sometimes hard to watch, there is a beauty to their tragic stories that keeps us mesmerized. They are bruised and real, and even if we want to turn away, we cannot, because we recognize their desperation in ourselves.

Dubus grew up with his three siblings and single mother in the tough, economically depressed mill towns along the Merrimack River in Massachusetts. He chronicles his childhood—his despair, his estranged relationship with his well-known father, his turn to violence and eventually writing—in his 2011 memoir, Townie. Over the years he has held many jobs that still allowed him to write: bartender, carpenter, house cleaner, halfway-house counselor, and teacher, all of which gave him a deep well of vivid detail to draw from for his fiction.

Dubus is the author of six books, including the New York Times bestsellers House of Sand and Fog, The Garden of Last Days, and Townie. His most recent book, Dirty Love, published in the fall of 2013 , was a New York Times Notable Book selection, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, a 2013 Notable Fiction choice from The Washington Post, and a Kirkus Starred Best Book of 2013. He has been a finalist for the National Book Award and has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, The National Magazine Award for Fiction, two Pushcart Prizes, and is a 2012 recipient of an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature. His books are published in over twenty-five languages, and he teaches at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Known for his gregarious and generous personality, Dubus’s candor and humor strike a sharp contrast to his dark prose. A beloved professor and devoted father and husband, Dubus fills his days with family, teaching, writing, and exercise, but as a self-proclaimed Luddite, he rarely depends on technology to help him out. We met in the Marriott in Boston in the midst of a snowstorm, out of which Dubus had to dig his car to drive to us from his home in the town of Newbury port. Because the weather delayed him, he continued to update us by phone , but never by text. To ensure the interview would be captured, we put many pieces of technology in front of him, a digital voice recorder, two smartphones, and even an old-school cassette tape recorder purchased from Radio Shack in the late 1970s. Dubus is on the record proclaiming his fierce vehemence against these new technologies. We began by asking him about the role of technology in his life and in the life of the writer.

ELIZABETH KEMPER FRENCH

We were talking about technology a few minutes ago, and I’m wondering what role it plays in your life and your writing.

ANDRE DUBUS III

None. I’m not getting on the digital train. I don’t have one of those (a smartphone) and never will. But I’m an asshole, because we’ll be at a bar, and I’ll say, “Come on, buddy. You’re terrible to own one of those, but while you have it, what’s the score of the game?”

I don’t like modern life—with these gadgets. I know there are advantages to them, and what writer doesn’t like the research capability of the internet? I remember I was writing a novel and wanted to know what gasoline cost in East Texas in 1941. I had to call the Boston Public Library long distance from Newbury port. A nice old lady answered the phone. “Just a minute, dear,” and she goes off to the stacks. Ten minutes later—long distance, waiting—”I’ll have to call you back.” Four hours later, I get the information. “It was seventeen cents, dear.” And now, in your underwear, within a quarter second, you can get that information. I don’t like how we’re all staring at screens. I cannot cell you how many times I will look up at a reading—and you know what it’s like, when you’re reading your work, it’s like you’ re opening your soul; it just feels so vulnerable—and someone in the audience is looking down at a screen. It’s like you’re trying to kiss someone, and they’re watching TV I think it’s changing us. Every night, everyone in my house is on a screen. Sometimes, it’s legitimate. My wife has a dance business, doing work. But she didn’t have to do that work before she had the computer; work only happened during work hours. My daughter has the iPhone glued—sewn—into her hand, and she texts a thousand times a minute. And my sons are on the internet doing all they do. So it’s a philosophical turning-away-from, and a temperamental turning-away-from. The older I get, the more simplicity I want. I don’t think these things have helped us. I think they’ve made us little rats, made us pay attention to little, stupid shit. I see this ad, and all these quick cuts, and the logo for the new gadget is, “Always connected.” But I want to be disconnected. I want nothing to do with being connected. I want to call when I want to call. And I’m not going to call.

FRENCH

What do you chink of the personas people create of themselves online? Especially on social media sites like Facebook?

DUBUS

I find that part poignant—that people need to show who they were before they’re dead. And I think they have every right to pick and choose how they’re going to promote that or express that. I’ll never do it. My publisher made me get a Facebook page a few days ago, but I’ll never go on it. I said, “Put this letter on there,” and I wrote: “Dear readers, I’m not a fan of this whole digital world, but I’m a fan of human beings, and so this is here for you to know where I might be, and if you want to come meet me in person, I would love to see you in the flesh-and-blood, eye-to-eye way. But that’s it. I’ll never be on chis again. Sincerely, whatever.” My wife’s got a Facebook page, which she doesn’t have time for, and I’ll look at the people on it, because how can you be a writer and not investigate a little bit? I’ll look and I’ll see that most of my friends who are in their fifties, for whom a family never happened—they fell through the cracks as wives and husbands. They’re going to die without having kids. And my heart goes out to these people, because my life began when I had kids. I think, They’re all alone. Why not reach out to people you haven’t seen for years? Why not? I’m not going to do it, but I’m not going to judge it. So, yes, I am a Luddite. I recently got a contract on the email that said just cut and paste and send it back this way. I wrote back saying, “I don’t know how to cut and paste.”

JOSEPH SALVATORE

Many emerging writers today are told by their publisher to promote their work through social media. The AWP conference is a viral place for mostly unknown writers to gather and network. Can you talk about the career versus the work?

DUBUS

I’m not criticizing. I know a lot of publishers are in peril financially, and so they’ve pushed this task onto us because they’ve laid off their publicists, and they’re trying to cut corners. I have to say, for me, this whole career consciousness is a kind of poison.

I think it’s a publisher’ s job to do all this shit, so I resist it, and I think we have every right to say, “That’s your job. You’re taking fifteen percent of every book, so earn it! I’m writing another one.” I really feel that way. But let me take that back, too; there’s a caveat to that. I’ve been fortunate enough to get some nice advances for the last few books, and so I’ll do a sixty-city fucking tour even though a book tour is a recipe for self-loathing. I’m very fortunate that I’m in the literary Boston community, because I’ve got a lot of good writer friends now, and while I didn’t always hang out with writers, I have a good chunk of them now, and they’re fun to hang out with. But I try to avoid any activity that makes me career conscious, because I am as susceptible to it as anyone. I didn’t want to be a writer to be a writer. I just like writing.

You read Townie, so you know I came to writing basically to save my life, and I was surprised it was in me, but it’s in a lot of us; there are six or seven writers in my clan. One of the benefits of being my dad’s son is I quickly realized no one was going to give me any positive attention whatsoever. The world was not only going to ignore me—it was going to kind of go after me.

I thought, I’ll just do it for me—no, not for me—for the characters who are coming. I’ll just show up every day. A day writing badly, or mediocrely, is a hundred times better than a day where we don’t get to the desk at all. I never lose sight of that fact that it’s a wonderful gift from the Divine, the Mysteries, whatever these things are around us, that I found early on something that, when I do it daily, makes me feel magnanimous toward humanity, keeps me curious, keeps me alive, and it’s been a wonderful happy accident that I actually had a career happen. Because that was never the plan. Early on, I couldn’t afford an office. There was no office at Emerson College. I was driving one day, thinking, Wow, when the radio’s off, this car ‘is pretty quiet. So I started to write in my car. I wrote all of House Of Sand and Fog over four years in my car. It was 5:30 in the morning—if it’s a carpentry day, I’m in my work clothes; if it’s a teaching day, I’m in my teaching clothes. I would get my coffee, go to the graveyard, pull up next to a grave. I’d open my composition notebook, sharpen my pencil with a utility knife, and I’d feel like sleeping. If it’s winter, I’ve got the car running with the heat on. If it’s summer, the windows are down and I’m wearing bug spray. I read a paragraph: “Ah, it sucks. Fuck.” Cross it out. Write two lines. Stare at them. Write three or four more lines. Write a paragraph. Ooh! Something’s starting to happen. Ah, fuck, time for work! And have to put it aside. But four years later, I had a book.

FRENCH

So did it take the full four years to write House Of Sand and Fog?

DUBUS

It took three years in the graveyard. At the end of that, I had twenty two notebooks with a beginning, middle, and end, and then I had to type it. I spent a year typing and revising. Then I sent it out. It went to twenty-four, twenty-five publishers over two years, which is normal. People don’t realize this. My first three books went to over a hundred publishers. Seven years of no’s to get those three yes’s. I also had the model of watching my father; his life never changed at all, whenever he had a book out. He also had a very small publisher. He would get some nice reviews, but he never made much money.I’m grateful for the material success I’ve had, but it’s been a happy accident.

FRENCH

I’m curious about writing in longhand. House of Sand and Fog was in different viewpoints. Did you find, over the course of three years, that it was difficult to find where you were? If you were in Kathy’s viewpoint, was it difficult to go back and find where the Colonel was? How did you manage that kind of multiple viewpoint, especially on paper?

DUBUS

Well, it wasn’t so much the paper as the lack of time I had to write. I just did a talk with Daniel Woodrell—Winter’s Bone—and before every writing day, he reads the entire manuscript before he writes the next sentence. If you’ve got two hundred pages—that’s four hours of reading—before writing the next sentence. So everyone’s got their own way. For me, and this may have helped, I knew I had thirty-one minutes, maybe, in the car before I had go to the highway to hit the job site or the classroom. I would reread enough to get back into character, and with the notebooks, it’s crossed-out lines and arrows and numbers. But here’s what I love about writing longhand: I built a soundproof cave in my basement, like a jail cell, five feet wide, six feet rail, eleven feet long. It’s got a little port window I cover with a blanket, a little desk, and a blank wall—and I’ll put on my headphones and I’ll play music and I’ll type the previous day’s longhand into the thing, and then I’ll turn off the music and read over the typed stuff, making revisions, and then I’ll keep writing longhand. I need the physical intimacy of flesh, blood, bone, wood, paper. It helps me enter the character.

SALVATORE

So you don ‘t listen to music when you’re doing fresh composition?

DUBUS

No. I have to have complete silence. I put headphones on that I used to use for my table-saw work. I can hear jackhammers or squirrels, but I can’t hear human voices.

FRENCH

Do you think it slows you down, in a way that’s helpful, to write longhand?

DUBUS

Writing longhand does slow you down. There’s a great line from Goethe: “Do not hurry. Do not rest.” Some people say, ” I need the computer, because my ideas are so fast.” I say, “Ideas? I don’t trust ideas. Ideas are just ideas.” I trust the other stuff. I love that line from Flannery O’Connor, from Mystery and Manners: “There’s a certain grain of stupidity the writer of fiction can hardly do without, and that’s the quality of having to stare.”

What I love about longhand is that when you look at that screen on the machine, every thing’s so fucking perfect, the margins, everything. It’s like having a partner you think you love—she’s so beautiful—but there’s really nothing going on between you. He’s so handsome and nice, but there’s just nothing happening. So every thing’s sexy, but I’m dead inside. The handwritten manuscript is homely; it’s ugly. It’s full of crossed-out words, X’s and numbers—read this first, then this and this, then arrow back four pages. It’s a messy pain in the ass, and when that starts to read well, you think, Well, there might be something happening here. So I would sometimes read twenty pages of mess, maybe five pages typed, and then I’d write in thirty-one minutes three sentences, and then I’d start the car and go. I like how it slows me down.

FRENCH

In your class at Emerson, you talked about the process of discovery when you’re writing a first draft, trying to capture what’s happening as truthfully as possible. Later, you’ve got a beginning, middle, and end, and you know it’s not there yet, but you have a sense of what happens, a sense of the conflict in the character you might not have realized at first. The characters slowly reveal themselves to you. So when you go back to revise, do you fear that you’re imposing something on the characters now that you’re more conscious of the work?

DUBUS

I love this Richard Bausch line: “If you think you’re thinking when you’re writing, think again. You’re much closer to the dreaming side when you’re writing, so just dream, dream, dream it through. Then when you’re done, try to look at what you’ve dreamed like a doctor looks at an X-ray, and cry to be terribly smart about it.” He’s talking about revision. I’ve stolen Janet Burroway’s distinction of story versus plot, and I use it in classes all the time, because I think it’s helpful, the way she elegantly lays it out: Story is a causal sequence of events, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. You have to give yourself permission to write through seventy pages of brush, where you know you’re kind of off the trail, and you’ve lost the scent, but you’ve got to write it to find your way back. You may not keep all that you’re writing about his history in dental school, but you’ve got to know who this dentist is, who’s married to your main character. Even though a little voice in your head says, “Ah, this is fucking really slow. This is such a—so what?” But you’ve got to find it. So what is plot? Plot, Burroway says, is how we arrange that causal sequence of events in order to highlight emotion, dramatic tension, theme, aesthetic, to make it more beautiful, to make it more fully itself. So go back to Bausch. He ‘s talking about that X-ray on the wall. Even then, he says, ”Try to be terribly smart about it.” I think he’s talking about plotting. And even then, it’s not a contrivance. Plotting is much a dream-like state; it’s more rational, analytical, and logical than dreaming, but it shouldn’t be too much that way. When it gets too much that way, that’s when you’re assuming, Oh, she’s a recovering alcoholic. I have to keep remembering that. But then I remind myself: Wait a minute. These are real people. I don’t think they’re just creations of writers. I think, when you’re writing well, you’re finding them in another dimension; it’s an act of spiritual excavation.

What distinguishes a good work from a great one, despite all the aspects of craft and all the skills you bring to it, is genuine curiosity. I’m speaking for myself. You teach what you need to learn. My worst writing has been when I have not been curious enough about the material. My best writing has been when I have been totally curious. He said this, but is it all that? She says this, but is this all she thinks about what she said? Is this all she feels about what she thinks? And is that all he said when she said what she thought, after she said what she felt? That Hemingway line: “Every writer needs a built-in, shockproof shit detector.” Why is my shit detector going off every time I’m in this really well written scene I wrote? I remember when I was in my twenties at some reading, and some famous writer said, “Oh, it gets harder as you go along.” I didn’t know it then, but I think he was saying that even though you’ve been practicing writing daily for decades and are more nimble than you were when you starred you can describe a woman sitting in a chair, with a light behind her, overlooking Boston, maybe a little more deftly than you could thirty years ago—but just because you write well about something doesn’t mean it happened. We get to be such good liars, we’re not writing the truth anymore.

When I write a story, I’m never gripped with the desire to tell the story. I’m gripped with the desire to find the story, to find it. You can’t choose what you’ll be pulled coward. Let me give you an example: For years, off and on, I’ve read in the newspapers about a certain kind of predator. He’s not a sexual predator, not a violent predator—just a guy who does something weird. And it’s always interested me. But, apparently, not enough, because whenever I’ve sat down to write his story, twice now as a novel, it collapses like a house of cards. I did a bunch of research and I wrote really, really hard. I’ve been writing long enough—and I read it. It’s a decent passage; it’s a decent piece of dialogue. Again, ch is the whole notion of: The writing’s not bad; I’ve been doing it a long time. But it feels … It took me years to start saying chis in writing classes: To me, there’s a difference between making something up and imagining it. Just because I want to write from the point of view of this guy doesn’t mean he wants me to be his daddy, doesn’t mean he’s going to come to me.

FRENCH

Did you feel less connected to him as a character?

DUBUS

I felt like an actor pulling off a decent performance. But here’s what happened. I go into his first victim, a woman working in a bank, kind of a pretty, overweight woman. So, okay, I’m going to hop into her point of view, just to find her a little bit, and then I’m going to zap her with my guy. I’ve been writing for three months from his point of view. With two paragraphs of writing from her point of view, she felt ten times more real than he did.This is the mystery I’m talking about. One of the dangers of fine art instruction in graduate programs—undergraduate, whatever, conferences—is that we can demystify the process too much. It’s mysterious to me why this overweight, lonely, pretty woman in a bank is far more real to me, in minutes of writing about her, than this guy. So, okay, I’m going to ignore that feeling. I’m going to keep writing, because I’m going to zap her with my guy, because that’s the fucking novel I want to write, and I’m going to write it! After maybe six days, two weeks of writing, it was so clear that her passage was imagined and real. And his was fake and contrived and better written because of it. Pascal said: “Anything written to please the author is worthless.” I really believe that. I don’t chink we get to do what we want to do. I believe writing is an act of humility, of opening yourself to something larger and allowing it in, no matter how you feel about it. So that lady turned into the first novella in the book coming up. She never even saw the guy again. He was like a Hollywood set held up by telephone poles. I let him go.

FRENCH

Have you had other characters you felt distant from, who you had to work harder to understand?

DUBUS

Lester in House of Sand and Fog.

FRENCH

His point of view is very brief.

SALVATORE

And it’s close-third, as opposed to the two firsts. What happened with Lester?

DUBUS

Here’s the thing: I know Sand and Fog became a big success, but I’m haunted by it. I think a better writer would have written a better book, and I’d like another stab at it. One of the challenges for me was Lester. I’ve got these alternating first-person points of view. Now, this is it again: back to mystery, right? The Colonel—I tried all these various points of view—he would not come, until I got to first-person present, which I didn’t want to write in, because I wrote a lot of my first book in first-person present. I said, “It’s too intimate, too close.” But he would always show up in the present. And then Kathy would only show up in first-person past. I tried all these points of view. Isn’t it weird that the only present-tense character in the book doesn’t survive it? He can’t tell it in the past tense. That was not conscious at all—just intuition.

When I get to Lester, Kathy’s in the house. She’s drunk and suicidal, and the Colonel’s gone. I’m thinking, Oh, this is great, man. This might actually be a positive thing for once in my writing life. But then, it’s fucking Lester, sitting on the porch. I kind of stared at the page for a while, and I just kept seeing Lester. I’m just staring and there he is. I see him waiting. I remember thinking, Fuck! I don’t want to get his point of view. I’ve got, like, a hundred and eighty pages in their points of view. Isn’t it kind of late to bring him in? I thought, I’m not bringing him in. I’m going to go back to them. But they were just in a tableau.

I kept seeing him on that foggy porch in the fish camp in the woods, waiting for her. I said, I don’t want to write about you, motherfucker, but I guess I have to. I went in with a first-person narrator, because I had this little rule in my head: You can’t go from two first-persons to a third. What the fuck? I have to do it first. So I did a first-present. He sounded like a bad piece of matinee cowboy writing. “I’m waiting for my woman on the porch. Where is my cute, little alcoholic sex … ” It was awful. I tried first-person past, and it was worse. I tried third-person subjective, but it was still a little more distant—the third. A little alarm went off: You can’t go to a third-person POV! And I thought, why not? All of a sudden, I could feel him. I could feel him far more than I could before, but I still felt, all the way through him, through this whole section, he was saying … With the two first-person points of view, it was two hands pushing this way: “Back off, Jack.” When I finally found the third-person subjective voice, one hand was saying, “All right, come on,” and the other one was saying, “Back off.” For a while, I felt like an artistic failure to not have both hands pulling me in, as I felt with Kathy and the Colonel, bur then I said, ” No, this is you, motherfucker. This is how you are. You’ve got a guard up, don’t you? You’re an inauthentic kind of dude. I’m just going to let you be.”

FRENCH

I recently looked at House of Sand and Fog and a few other multiple-viewpoint novels for what I’m writing now. I was trying to organically follow all my characters’ voices, how they spoke to me, and was concerned the points of view weren’t all marching. I had that same moment of—Really? Am I allowed to do that? So it was helpful to see what you had done, mixing first-person past, first-person present, and third-person past, and say, “Oh, sure, you can do that.”

DUBUS

That’s why reading is so important for writers. I’m mystified when I hear people say they don’t read when they’re writing. Are you kidding me? I remember hearing this story about Richard Yates at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and I heard my father say it years later—that he had two points of view in the same sentence, and everyone said, “Oh, you can’t do that!” And he said, “Well, I just did.”

Again, that great line from O’Connor: “The writer can do whatever she can get away with. Unfortunately, none of us have ever been able to get away with much.” This notion that the art is larger than the artist, that there’s such a thing as dramatic unity, and effect, and aesthetics, and some things hold, and some things don’t. It’s endlessly exciting. I’ve been doing this for—I don’t even want to say it, because I’ve only published five books—but I’ve been doing this for thirty years, five, six days a week. The only time I didn’t was when we had our kids. For, like, three days I didn’t, and then when I had pneumonia twice. I’m as excited about it as when I began, because it’s such a descent into the unknown. It’s scary and exalted, and I love stepping into the not-knowing. I think one of the dangers of being a successful writer, in terms of books and publications and money and all that shit, is I think you can run the risk of becoming more a thinker than a dreamer. I’m trying not to do that.

SALVATORE

I’m going to return to Lester for a moment. At some point, he takes the bullets out of the gun and gives them to Kathy. And at one point, he thinks, I could have told that kid, “It’s not going to work; there are no bullets in there.” And he might have stopped the whole thing from going down. You talk about struggling to create Lester. But Lester was probably, in terms of Greek tragedy, the one that scared me the most, how easily you can go from being an upstanding citizen to falling in ways you never could have imagined.

DUBUS

The truth is, the inauthentic feeling, I ultimately concluded, was him. He did not feel like a contrived character to me, or I wouldn’t have left him in. I would have rewritten the whole rest of the book. I am mortified to say that there is so much Lester in me. I’ve never been a cop, I’ve never had a gun, but it is no stretch for me to imagine going from being an upstanding citizen to some guy in a jail cell.

FRENCH

And to save the victim, right? That’s really what he was doing. He was partially motivated by saving a woman, who he felt something terrible was happening to.

DUBUS

Which brings me back to this notion of imagining versus making up. I’m writing from her point of view, but at first I didn’t know she was an alcoholic. I knew she was a cokehead, but I’ve met cokeheads who could drink, I’ve met alcoholics who can do a line of coke, but not go down the coke road, and then there are those who have dual addictions. I thought, Maybe she’s not an alcoholic. Maybe her husband was alcoholic and into cocaine. Maybe she’s just a recovering cokehead. Lester’s pouring the wine on that date, and she’s drinking, and I was actually surprised to see it escalate. She’s drinking nips of Bacardi, and now she’s going down the spiral, and she’s at the gas station , getting gas. I’m following her, thinking, All right, so I’m shitfaced, and I’m fucked up, and this mother fucker’s taken my father’s house, and I’m the fuck up of my family, and I see the gas is empty. I wasn’t like: I will now send her to the gas station to get gas to burn down the house. I go get gas, and I see it with Kathy—Motherfuckers, we’re all going down. I’m filling the gas container, and then I go to put it in the trunk, and I see the gun. I forgot the gun was there! She’s looking at it; I’m looking at it over her shoulder, kind of in her skin. We reach for it, and I’m thinking, What the fuck’s going to happen now?

Stephen King says, “To me, these books are found objects.” I thought that was really remarkable and true. But look, none of that can be taught. Ron Carlson says: “Details are for the writer only. They are the instruments by which we steer.” So many younger writers think, Oh, yeah, well, I’ll give him a job later. What do you mean, give him a job later? Are you kidding me? A guy who comes home from working on hearts in an operating room is a different human being than someone who’s been shoveling shit—a different human being than someone who’s been changing bed pans or bundling mortgages and sending them to Taiwan. You must know what your character does all day. Not just that—sensory detail is so important. We all know, we are more in the room than someone who’s blind and deaf. They’d be in the room in a different way; they have other gifts that come out, but they are not in the room as fully as we are, because they have been robbed of two important senses.

When I write, I’m not bringing in all that sensual detail so much to give the reader a felt experience, although ultimately I do want to give the reader that experience. The main reason I’m bringing in all that detail, though, is so I can be in the body and in the moment with this character to know what’s really going on. Let me give you an example—I’m writing from the point of view of Kathy. I’m waking up in my car. I’m sleeping outside the house that was wrongfully taken from me. I’ve got to pee, and I’ve got to brush my teeth. But I’m hearing power saws. Now, I know that they’re circular saws, because I’m a carpenter, but she’s hearing power saws, and she looks out and there are carpenters, cutting into the roof of her stolen house. Even with the bad taste in my mouth and having to pee, I am now running barefoot across the street: What the fuck! That’s my fucking house! I’m running with her, and what do I see? An upside-down piece of roof sheeting, with a bunch of roofing tacks sticking out, and she steps on it, nine little holes going into the bottom of her foot. She pulls it out. As soon as that happened, as a writer, I’m thinking, Ah, fuck! Now every time she’s in a scene, I’ve got to remember her foot. The writer could say, “Well, fuck it. Maybe she just stubs her toe.” But that would be making it up instead of imagining it. What your imagination gave you was the sheeting with nails, now work with it. Summon the nerve and the faith, and work with it.

Now what happens? Well, one action stories a causal sequence of events with a beginning, middle, and end. Or that causes them to come down. She’s in the house, getting her foot wrapped by this Iranian lady who doesn’t even know who she is, and it’s sweet. Now I’m in this motel room with my wrapped foot, that’s been wrapped all day with an Ace bandage on a hot day. There’s this guy who I, as a writer, don’t know who the fuck he’s sniffing around. I don’t even want him in the story. Why? Because I don’t want to research cops. But he’s sniffing after this woman. I’m not trying to judge, but I’m just allowing him to—okay, here he is. He walks over. She’s unwrapping her foot, because it’s hot, and as she’s starting to unwrap it, she’s afraid it’s going to smell. And that’s right when the handsome, young cop is there and, frankly, she doesn’t know it, but nobody wants to smell bad. She sits back so he doesn’t smell her stinky foot, and when she sits back, he takes that as some sort of invitation to sit on the side of the bed. She’s leaning forward to get more comfortable and then they’re kissing, and then they’re fucking! And I’m writing this thing: Aw, come on. Bullshit! And then I think, Come on! What kind of a prick are you? And then: What is this? What are you, like, a sex addict, too? This is so fucked up. And the next day, my shit detector did not go off. Now I’ve got this cop in my story. That whole novel never would have gone to its catalytic, tragic end, without the introduction of that cop and his gun, which never would have happened if she hadn’t stepped on nails.

SALVATORE

Cause and effect.

DUBUS

That’s all I try to impart in classes. I say, Look. Anyone’s invited to this party; you just need real, authentic curiosity, an ability to dream, and concrete, specific sensual detail. Put those together, and it always leads to characters in trouble. Why? Because everybody’s in trouble all the fucking time. This is another thing that upsets people, especially Americans: All three of us—hopefully none of us have big trouble, but if I scratch the surface a little, we all have some trouble. That’s normal, and that’s where stories lie.

SALVATORE

So when Lester sleeps with Kathy, at what point in the writing do you have to figure out why he’s having trouble with his wife, and when and if the backstory with him and his kid will come into it? What’s the relationship between revision and continuing to tell the truth?

DUBUS

I tend to write chronologically, and I allow cause and effect to happen. That’s not to say that the finished story will be in the shape in which I wrote it. With Lester, I begin where I think he begins in the book, which is, he’s waiting: Where is she? She said she’d be here. Why isn’t she here? I just left my wife. It’s like people: some you’re just more attracted to, male or female. You just get along. With Lester, I didn’t want to hang out with him. I would rather hang out with the tyrant, the proud, rigid Colonel.

Actually, let’s talk about the Colonel and then do Lester, because the first few weeks of trying to write from the point of view of this Iranian guy, he wasn’t showing up, and I finally figured out why he wasn’t showing up. I found the first-person voice pretty soon, but he still wasn’t showing up. I realized I was judging him. I realized I thought, You’re a prick. You were with SAVAK, the CIA-controlled death squads. You were a piece of shit. You’re just some powerful bastard. It was totally unconscious on my part. There’s that great line from Hemingway to Maxwell Perkins at Scribner’s. He said, “You know, Max, the writer’s job is not to judge, but to seek to understand.” I wasn’t seeking to understand, but I thought I was. Again, it’s like convincing yourself you’re kissing her and you’re really turned on, but something’s not happening. I had this plywood desk I built in our little apartment and I was staring at the plywood. I cut it with a dull blade, and it was a shitty cut, and I was thinking, You don’t do anything right. You don’t go get a sharp blade. And then thinking, You know what? You’re judging this motherfucker. And what happens in life when you feel prejudged by someone? You say, “Fuck you.” I think the same is true of characters. He felt prejudged by me, and he said, “Fuck you.” So I’m looking at this shitty jigsaw cut, and I said, “Why don’t you really try to understand this guy?” I remember asking, “What’s it like?”

Charlie Rose asked Mike Nichols, the director, “What’s the main question the storyteller asks?” Nichols said, “Well, it’s not the main question the newspaper reporter asks. The main question the newspaper reporter has to ask before writing his or her story is, ‘What happened?’ What the storyteller asks is not, ‘What happened?’ but, ‘What’s it like? What’s it really like to be in this thing that’s happened?”

So now I’m going to be more open, less judgmental: What’s it really like to be a guy like you, from your culture, working with these blue-collar people? As soon as I felt myself embrace genuine curiosity, he showed up, and he stayed. The same thing with Lester—you asked about Lester’s marriage and all that. I had far less judgment against Lester. I was just a little irked that I had to go to the third-person point of view and to another character two hundred pages into the story, but that’s what was presenting itself. It was a much shorter trip to genuine curiosity about Lester, but I remember thinking, Okay, who are you, anyway? I called the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Department, and got a hold of a Captain John Wells. I probably made twenty calls to him over the next few months. It was a matter of: What’s it really like to be a field trained officer, seven o’clock, after a twelve-hour shift training younger cops, just left your wife, you’re on the porch, you’re kind of horny and lonely, probably hungry, and you want a drink, and she’s not here. You had that sweet kiss—just the one. And now, it’s like acting: Where is she? And now I’m in the car, driving, going into Lester.

FRENCH

Writing a novel takes such a long time—so much of it spent in that dream state you spoke of, not knowing your characters yet, not knowing where you are going.

DUBUS

Yes, no matter what’s going on in your life—a novel can take a long time. That one took four years; The Garden of Last Days took five-and-a-half years; Bluesman took three years; The Cage Keeper took six years; Townie I tried to write for twenty-eight years, three different times. You’re going to go through all sorts of highs and lows and changes in those years, but your novel doesn’t. This whole notion of imagining versus making up: I cannot tell you how many sex scenes and meal scenes I’ve written, drinking scenes, that I cut. You’re bringing yourself to the characters, but you cannot bring your literal life to the page; you have to find a way to begin to turn it over to them. I think some of the sex is too explicit in House of Sand and Fog. I mean, there’s this blowjob. Why do I need that? But I remember why I wrote it so explicitly, and I actually cut two or three moments from that, because I needed to find out what they had together. I still am not sure. I think there was more needy, addictive sex than lovemaking between them, but I needed to write it explicitly to find out. I could feel her need for him. I felt a lot of addictive, desperate need, and not a lot of love.

SALVATORE

I remember thinking the scene with Lester and Kathy was about disconnected intimacy from his wife, a dearth of intimacy for this guy. So he comes together with this woman who might be looking for a connection through sex. It’s the moment they both have, a collision that was honest, albeit damaged.

DUBUS

I’ve met couples over the years who are companions, or lovers. I can’t tell you how many marriages I’ve seen where they’ll tell you they haven’t had sex in five years or something, and they seem to have a solid union. You know where Lester came from? One of the things I cut out of Townie was—I went to Mexico with a bounty hunter, looking for a contract killer. I was twenty-two and had a fake name, and the guy was a bad, bad guy. We went to gay bars, bisexual whorehouses, because he was bisexual. I was meeting with US Marshals and FBI agents, DEA guys from New York, and the Colorado Bureau of Investigation. One night, three in the morning, I’d done some surveillance on a diamond thief. I actually did this for like six months, and it was interesting, but I cut it from Townie, because Townie had its own narrative arc. This felt like a whole other narrative arc. So I cut it. I was a quiet boy, just listening and sitting across from a US Marshal, who had just come from a raid that night. He had this crooked mustache. He was kind of handsome. He looked more like an English teacher than a US Marshal. He looked like he shouldn’t be carrying his gun. He was talking tough and almost blew off this guy’s head, but I thought, This guy looks like he should be teaching Ezra Pound somewhere. Fifteen years later he shows up in my story.

FRENCH

You just said you were a quiet boy. My interaction with you as a student, or later if reading an interview or catching something that you’ve done over the years, always showed you to be this incredibly gregarious, open, warm, no-boundaries person. So I was struck by the Andre in Townie, who seemed much more solitary and introspective, even brooding. How do you connect those two parts of you to being a writer?

DUBUS

When you talk about those two selves, the truth is I was scared. Writing Townie brought that back, and educated me to that conscious fear. I spent most of my youth afraid. I was afraid all the time. I was a bright kid, and I was in blue-collar neighborhoods, where articulate, bright kids get stomped, so I always hid my smarts the way a lot of women do.

I got back in touch with me writing Townie: I was physically small, sedentary, weak and terrified—and bright and depressed. Then all the suffering changed, and I willed my way out of it. I became violent, and then I became who I always was. I think if I’d grown up in a safe environment, the way I’m raising my kids, I would have been the class clown. I would have raised my hand. I wouldn’t have been ashamed. I once wrote a paper on Walt Whitman that I snuck to the teacher, because I didn’t want anybody to know I wrote the paper on the homosexual poet. I was up till three in the morning, making it really good. I didn’t do a lot of homework. I wasn’t a good student. But I loved Leaves of Grass.

It was learning to defend myself that I fought my way onto my own two feet. So, you know, motherfucker, I deserve to be here, too. What do I mean by “here”? On the planet. My brother was really hard to write about in that book. I took a more traditional male route, where I rook all my hurt and converted it into rage, and I became homicidal. If I’d been an athlete, I could have taken that rage and thrown a football or swung a bat, but I used my fists and feet. My brother did what a lot of girls do—which is a generalization, but I think there’s some truth to it—he took all his hurt and rage and turned it inward. He got depressed and sick and wanted to die. I felt it was important to have his suicidal route and my homicidal route. But it was my homicidal route that led me to the nerve it takes to write.

I don’t know if I’ll put this in the book, but I’ve been thinking about it since. You know when I write about that membrane? Joe and I just met. If l reached out and touched his cheek, I’d be violating his personal space. But it was in that first fight that I really found out what it was. I saw a shoving match between two fathers at a kids’ hockey game a few years ago—”Oh, yeah? Oh, yeah?” They’re pushing and shoving each other in the parking lot, and I looked at them, and I thought, Neither one of them is a fighter. Neither one, because there’s no foreplay in fighting. None. We’re in it—BOOM! My point is, anyone can learn to throw a punch, and it’s good and it’s valuable, but for experienced fighters, it’s like a psychological hymen, and once you break it, it’s always broken. Once you punch someone as hard as you can in their face, you’ve learned to violate the intimacy of another human being, and you’ll always know how to do it. And, frankly, it’s hard not to reach for that. It’s like having a gun; it’s like having a nuclear bomb.

I’m not going to belabor everything that’s in Townie, but I don’t think I wrote about this directly, and I’ve been thinking about it. I’m an uncle figure for a lot of young people, and one of them is a young woman I’ve known since she was a kid. She’s twenty-seven, twenty-eight now, and she’s got a boyfriend who was a brawler from Haverhill—real rough kid. He and I were drunk one night, and kind of reminiscing about fighting, and I was a little ashamed, because I was really reminiscing. We both admitted we kind of miss that moment right before it’s going to happen, where you’re squaring off and you might get killed. There’s such an adrenaline high to the physical combat that’s about to happen. You don’t know this guy; you don’t know how dangerous he is; you don’t know how much crazier he is than you are, and it’s up to you and your body to get out of this. There’s a real thrill and a nerve to step into that unknown. You talked about the quiet me, and, yeah, I am outgoing and gregarious. I was always, but I was afraid to be that way, because I would get stomped. Once I got through the violent years, I realized there’s a similarity between the nerve it takes to step into a combat situation and the nerve it takes to try to enter the skin of another human being with a pencil.

SALVATORE

Another membrane?

DUBUS

Another membrane—when you go, Why can’t I be her? Why can’t I go all the way?

FRENCH

Are you saying that gaining nerve through violence helped you have the nerve to imagine yourself as a writer?

DUBUS

I’m hesitant to say this out loud, because I don’t want any young man or woman thinking, I’m going to go kick some ass so I can be a writer. I don’t think anyone’s going to take it literally, but the truth is, with my little path in life, it’s hard to imagine that I would have found writing any other way. I had to fight my way onto my own two feet, to stand there and plant myself and say, “You know, I’m not a piece of shit. I have a life, and I’m going to live it.” Once I worked through all that and survived physically and didn’t hurt anyone too bad, I think I did find myself in a place where I thought: Okay, now I can start. But it was totally unconscious.

SALVATORE

There’s something about the way you’ve talked about your writing ritual—a daily act of trying to become the other, your own relationship to a Creator, even your atheism—which suggests a spiritual side. Is that side connected to your art? I was thinking about your father’s daily practice of Mass and then writing and running.

DUBUS

Let’s talk about the ritual. Because I think that’s what you’re talking about more than anything. I reread an essay of my dad’s recently, maybe “A Father’s Story,” in which he writes, “Belief is believing in God. Faith is believing that God believes in you.”

I do not believe there’s a God who loves you. I do not believe there is a loving Creator who knows me and loves me. I feel deeply alone, and whatever good happens to me comes from my hard work, and that’s it. I think there’s value to feeling alone. So there’s that versus ritual. If you look at the word “ritual,” it comes from the Latin ritus: it means “river.” When you step into ritual, you’re stepping into some ancient river. I have pagan rituals, and I’ve never told anyone, but I’ll just share it with you. I’ve got to have a cup of black coffee—dark roast, French Roast, organic. Black. I begin each writing day reading poetry. I’ve got about four hundred volumes of poetry, and every time I do a reading in a bookstore, I buy a book of poems. I love poetry; I don’t write it, but I love it. Right now, I’m reading The Great Fire by Jack Gilbert. If I’m procrastinating, I’ll read six or seven poems, and I might read two poems, back to back. Then I’ll sharpen my pencil with a blade. I’ve never told anyone this, but I’ll tell you: My wife—I’m hesitant to do it. It’s funny how we don ‘t talk too much. Fuck it. If it has power, it’s just superstition, but it’s so interesting the superstitions here, because, again, there’s a great line in ancient Chinese: “If the mad dog comes at you, whistle for him.” My wife gave me two stones: one’s a piece of quartz that represents love, and the other is a piece of aventurine—green—that has to do with creativity. I hold those two stones in my left hand the whole time I’m writing.

FRENCH

Even when you were in the car, did you do that?

DUBUS

No, and not when I’m traveling, I don’t bring the stones, because I’m afraid of losing them. They stay in my cave. But also, one of the first writers who really influenced me was Breece Pancake. Have you read his story “Trilobites”? I turned a friend of mine on to that story—he’s actually the bounty hunter I worked with, and in his world travels he found a fossilized trilobite, and sent it to me. The trilobite’s on my desk, and then a dear brother of mine, who was an artist, brought me back a bottle of water from the Delphi Oracle in Greece. That’s been on my desk for twenty years. I write with these stones in my hand; I write with a sharpened pencil; I have headphones on, for complete silence; I have the Delphi Oracle water, the fucking trilobites; the ghost of Breece Pancake; and then, lastly, there’s a little piece of alder wood that my cousin put two holes in, and now it’s a pencil holder. That’s on my desk, too. And my Mead composition book. I am all about ritual. I’m a pagan. I ain’t no Catholic.

I remember when Doctorow said he writes in front of a blank wall. He said the only reason he doesn’t write in front of window, or in front of a photograph or painting or inspiring quotes is because that blank wall makes him go back to his sentences. I write in front of a blank wall. But I really am merciless about my mornings. Mornings are the dream time.

FRENCH

Early mornings?

DUBUS

I’m not an early dude. I’ve got to get my eight hours. I go to the university twice a week, and I don’t have to be there till, like, two in the afternoon. I’ll get my two youngest to their high school, Fontaine’s at her dance studio. I get my coffee, go to my cave, and I’m there from 8:30 to about 11:00, and that’s it, and then I go about my day. Sometimes it’s not that long. For many years, my magic writing time was an hour and fifteen minutes. That’d be about fifteen minutes of staring, then about twelve minutes of foreplay, then about forty minutes of hard work, ten minutes of cool down, thinking about lunch and phone bills. You’re out of there. But you can get a lot done in seventy-five minutes a day.

I’m not convinced more time is helpful. My old man, when he was crippled, had a tiny end table where he kept his medications, reading material, ashtray; he was laid up for months. He asked me to build him a larger table. I built one out of pine, three times the size. So he put his medication there, his book. In a week, that whole fucking thing was full. I said, “Dad, why do I have a feeling that if I built you a six-foot table, that’s going to be equally full?”

SALVATORE

We were talking about the quiet kid who comes through the fire, but I’ve been thinking about the spiritual side of you and this thing you do. Not only the feminine side I think I see, but the teacher. You can really quote stuff—not only quote it, but you live it; it’s not an act. And you’ve got so much committed to memory. I feel like some of this scuff suggests a kind of secular ritual, where these are almost like prayers for you, secular prayers. You have so many of those. Was that a part of the way you were reaching yourself?

DUBUS

I have poems memorized. For that reason. They really are like secular prayers. I think I retain what helps me, and I think what helps me is when someone has articulated what I’ve intuitively felt and never known. Then the words are there for me to give to someone else, if it’s helpful to them. I do say, often, that I’m full of shit in so many ways, but what I really mean, where I’m really full of shit is I talk like an atheist, but I feel like a holy man. So I feel like a fraud. Instead of the holy man who’s the fraud, I feel like the secular guy who’s a fraud. I knew a woman who was going through a horrible time. She was raised Irish Catholic, and she doesn’t pray, she said, “Because I don’t believe in God, and I think it would be hypocritical of me to pray now that I need him.” I said, “That makes sense.” I said, “You know, I pray all the time, and I don’t believe in God.” Right now, my son’s driving from Ohio to Florida with a bunch of frat boys to party all week, so I’m praying my ass off about that, because I have to. But the truth is, I do believe—and studies have shown—people fighting cancer. You’ve heard of this study? They had two groups. One group of people fighting cancer were prayed for by five hundred people—they didn’t know they were being prayed for—and another group was not prayed for. The group that was prayed for, eighty percent did better than those who were not prayed for.

I have a hard time believing in a strong head honcho. I don’t believe it, and I don’t believe there’s a God who knows my name. I’m a nameless speck. But I’m a sacred speck, as you are a sacred spec k. Have you read “The Magic Show” by Tim O’ Brien? There’s a wonderful line in there: “Writers tend to be the kind of people who want to enter the mystery of things.” I think that’s true of readers, too.

SALVATORE

The kid in Townie was scared, as you said. He was traumatized. And I’m hearing about different spiritual aspects in your life. This sensitivity strikes me as a characteristic of people who suffer from PTSD; one of the characteristics of PTSD is a hyper-awareness to the world.

DUBUS

Yep. I was in a Mexican restaurant with my wife, Fontaine, about five years ago, and something was really weird about the dinner. First, we were having a date, just the two of us, and then I realized, Oh, wow. I’ve got my back to the restaurant. I hadn’t sat like that in twenty years. I said, ” Honey, my back’s not to the wall.” She said, “You Want to switch?” I said, “No. I’m going to do it. I’ll have another round, though.” Writing Townie rustled up some emotional sediment. I feel post-trauma coming back. Every day before I work out, I’ll do this joint-loosening warm up that’s part martial arts yoga, and I’ve got my eyes shut when I do this stuff, and I see the workout I’m about to do. For ten or fifteen years now, I can shut my eyes in a gym; since writing Townie, I can’t shut my eyes. I shut my eyes, and I feel some body coming after me to fuck me up. So my eyes are open again. I am always standing in a room, scanning it.

FRENCH

So writing this memoir wasn’t healing in some ways? Instead, it brought everything back?

DUBUS

It was both cathartic and wounding; it cleansed me and fucked me up. I think maybe one reason I try to describe the scene in a precise way is I need to know where I am in the room.

FRENCH

In one scene in Townie, there’s a full paragraph of sensory description—I think it might be at Salisbury Beach.

DUBUS

I read that last night at the Literary Death Match.

FRENCH

It touches every sense, and that happens so much throughout Townie. I wonder if it is a way, like you said, of grounding yourself, but it also does the same for the reader—because Townie isn’t as linear and cohesive as your novels are; it’s fragmented, a little more reflective of memory.It jumps back and forth in time and age, but it also grounds the reader in setting and scene. I would read a paragraph or two—sometimes it would just be sensory detail—and as a reader I knew exactly where I was: sound, sight, smell.

DUBUS

First of all, my memory’s not that good. Words, quotes are in my head, song lyrics are in my head, poems are in my head. I can see a movie tonight, and I won’t remember it next month—it will be a new movie. I forget what happens in books, too. I remember lines, but I won’t remember stories. So how can I write a memoir? This I find really poignant about human beings: If you look at the word “to remember,” it means the opposite of”dismember.” Chop, chop, chop. To remember means to put back together. Which is why I believe the better memoirs for me are the ones where I feel them sincerely trying to put something back together. Once again, what’s fueling the writing, even though it’s about your own life, is curiosity. Like, I know what happened in my childhood, but What the fuck happened?

FRENCH

We were asking that question, too, of you: Is this really writing by discovery? If you already know the story?

DUBUS

Go back to Mike Nichols’s line: “What’s it like? What’s it really like to be in this thing that’s happened?” What I found about writing Townie was: Okay, thank God, I’m off the hook for having to come up with the events of the story, the way we do with a novel or short story. I know the events: That’s the night I got my ass kicked, and I almost got beaten to death. If the cops hadn’t shown up, I might have died that night. My creative powers are free to try to capture, What’s it like? What’s it really like?

Back to sensory detail: I find at least three in each scene to activate it. But with Townie, I used it as a way to open my memory, not consciously; I just noticed that it kept happening that way, so I kept it up. I’ll give you an example: I write about Old Newburyport, which really was a tough, ugly, abandoned waterfront town. I met a guy at the gym last week, who’s ten years older than me. He said, “My name’s Bruce. I grew up there. No one could fucking walk down that street. You’d get your ass kicked. Even if you lived on that street.” We were talking. I remember staring at the page, seeing how isolated my brother and I were, how we were the new kids, and it was a tough town, and all the kids were cruel, and we had no uncles and no father around and no mother around—because she’s working fourteen hours a day—and we would sit on the stoop. So, I’m going to write about sitting on that stoop on a summer day. What’s it like? What’s it really like to be in this thing?

I tried to capture the hot sun, and then the smell—that fucking broken sidewalk in front of our little house always smelled like dried piss, from the drunks who would stumble home from the barroom. A drunk really did wander into our foyer and piss on the floor. Here I am, the older writer, remembering forty years earlier: I could smell the hot piss, the dried piss, and now I smell this sweet smell on the paint. The older writer knows it’s lead paint, flaking lead paint. I’m trying to describe two smells and the feel of the hot sun on our faces, and then, all of a sudden, a panel opens in my memory: Oh, yeah! One of those days, Cody Perkins and those three guys see us, and they start chasing us. And now, Yeah, we fucking ran! Oh, that ‘s right! We ran through the lumberyard! I remember, We jumped over the fence! We got away! We went underneath the pier. Oh! That’s when the fucking drowned guy gets pulled out! When I sat down to write that day, I wasn’t thinking, This is the day I write about the drowned man to show thematically the danger of mortality. I just remembered: What’s it like to sit on that fucking stoop? Back to Ron Carlson: “Details are the instruments by which we steer.” That writing session ended with us walking underneath the pier, where I wanted to stay until dark to avoid those guys, but we didn’t want to see the dead guy. All of it I’d forgotten until I wrote that. What triggered it was genuine curiosity and sensual derail, which opened panels into my memory.

FRENCH

That makes me think of the Nadine Gordimer quote: “Writing is making sense of life.” Because you went back and discovered and relieved these memories and could maybe look at things more objectively, did you make more sense of your life?

DUBUS

I did. I needed to put the pieces back together to become more whole. I think something shifted, changed. Probably the whole time I was writing it, I thought, This is not going to be a book. It’s just too private. But I’m turning fifty. Richard Dreyfuss has this great line: “When you’re turning fifty,” he said, “you’re probably closer to your grave than your high school graduation.” I felt, this is going to be for my kids. They’re going to know me better, and they’re going to know where they come from better. I thought, I’m not going to make this a book. That freed me to write more honestly. I saw Mailer in an interview once, it might have been with Dick Cavett: “So, Mailer, you’ve lived such a large life. Why haven’t you written a memoir? You have so much co write about.” Mailer said, “I don’t think writers should write memoirs.” And Cavett or whoever said, ” Why?” This spooked the shit out of me. Mailer said, “I think a writer’s childhood is like a piece of quartz. In every play or novel that you write is light you shine through the quartz at different angles, which has its own spectrum of colors. I’m afraid if I write directly about the quartz, I’ll lose my art.” So I’m thinking, Fuck! What am I doing to my quartz? And then I realized, if I never write another word of fiction again, if I’m all done, well, I’m all done, because I so need to tell this story. Then I thought , You know what, Norman? Aren’t there other quartzes? What about the quartz of being a husband and father? What about the quartz of being a teacher? What about the quartz of being a carpenter?

Finishing Townie put something behind me. I’d already noticed something weird happening: I’ve never been able co write about the Merrimack Valley in my fiction. All my fiction is based somewhere else. My old man set all his stories in the Merrimack Valley. I remember ch is interview with Updike, and he called my father the Bard of the Merrimack Valley. I remember reading chat and thinking, He wasn’t the Bard of the Merrimack Valley. He doesn’t write about this place. It wasn’t a criticism; it was an observation. Maybe Kerouac might have been a little bit the Bard of the Merrimack Valley; maybe Greenleaf Whittier. My father’s art was formed in some mysterious way, the way all our art is, through the circumstances of his childhood: in 1930s-’40s French-Irish Catholic south Louisiana. Catholicism was huge. Being a Marine was huge. Then the ’60s come—that went into the pot. All the other mysterious forces created Andre Dubus’s art. He finds himself living in New England, this displaced Southerner, and he sets his stories in the town in which he finds himself, because that was his artistic inclination. But he never wrote about the Merrimack Valley. He set stories there the way Faulkner set stories in Yoknapatawpha County. It was his Yoknapatawpha County, but I felt like he never wrote about this place. There was no frustration—well, there was a little bit of frustration, but not much—I just thought it was really inaccurate of Updike to say that.

Since writing Townie, this accidental memoir that comes from an essay about baseball and my son—these novellas I’ve coming out in the fall are all set in Merrimack Valley. It’s like I had written about it literally, having grown up there, being a mill town kid, from an educated family, and now I’m free to dream about it. I couldn’t do that before.

FRENCH

You had one story in The Cage Keeper that’s highly autobiographical.

DUBUS

“Wolves in the Marsh.”

FRENCH

Was that harder for you to write at that time?

DUBUS

Yes. John Irving said, “I think that there are at least two kinds of writers: Those whose vision is more somber and tragic, and chose whose voice and vision are more comic.” I think about other differences between writers: Those who are more painterly, and those who are more auditory. Hemingway was painterly; Faulkner was auditory. It’s all about voice and language with Faulkner. With Hemingway, if you gave him some brushes, I bet he could have painted. Then there are writers who can create fiction directly, derivatively from their lives, and those who cannot. My father, Truman Capote, Ernest Hemingway, just to name a few, could write derivatively from their lives. My father’s vision was narrow and deep— extremely deep—but he wrote derivatively from his life. I recognize ex-wives. I recognize us kids in his work. I recognize friends in his work. A friend of mine read my first two books and said, “Where are you in your work?” I said, “I don’t want you to know. I’m trying to be these people.”

I don’t think one is better than another, but I realized, finally, “Wolves in the Marsh” was hard to write because it was too derivative. I’m not a writer who can write from my life. Townie I tried to write three times as a novel. I probably put eight or nine years of writing into it. First it was called Lie Down and Make Angels, and it was terrible. Whenever the father figure came out, based on my father, I made him look worse than he was. The mother: I made her look worse. Whenever little Sean Dolan appeared—me—I made him look better than he was. It was dishonest. Capote says, “A writer must write as cool and detached as a surgeon.” I didn’t have the detachment. Finally, I was able to write it as this accidental memoir, and it has freed me, in some ways. I have wrestled some things into place inside me, but nothing simple, because my post-traumatic stress is back again.

SALVATORE

Can you tell us a little bit about the forthcoming novellas? You talked about how you’ve shifted a little. Are they more autobiographical, other than just the geography?

DUBUS

No, they’re not. The book’s called Dirty Love. One story is from the point of view of an eighteen-year-old girl and the eighty-one-year-old great-uncle she lives with. Another is from the point of view of a fifty-six year-old man whose wife just cheated on him, and their marriage is going down the tubes. Another is from the point of view of this woman looking for love. Nothing directly autobiographical, but I realized … Here’s a beautiful line from Willa Cather: “A writer is at her best only when writing within the character in range of her deepest sympathies.” I asked myself, Where are my deepest sympathies? I don’t like global warming! Homelessness is mean! No! It’s only after you’ve written something that you discover the answers, right? I’m thinking about Bluesman: It was the third novel I wrote, but it’s such a first novel. It’s overwritten, and what haunts me most about this book when I look back-the guy who directed House of Sand and Fog said about Bluesman,”It was an okay book, but it didn’t seem like your book.” I realized I wrote that book outside the range of my deepest sympathies.

There was a lot of me in that Iranian military man in House of Sand and Fog, there was a lot of me in addictive Kathy; there’s a lot of me in fucked up Lester. I was trying to put a lot of me into these characters, but it was more from the outside in Bluesman. I am haunted by that book, because I feel as if l wrote it outside the range of my deepest sympathies. It’s all subconscious; it’s all the dream world. Again: imagined versus made up. You only know that when you are with your center, when you hold the stones, and sharpen the pencil, and stare and wait.