February 10, 2017

ALIA BALES, CHRIS MACCINI, MATHEW MAPES, & KIMBERLY POVLOSKI

A CONVERSATION WITH PAISLEY REKDAL

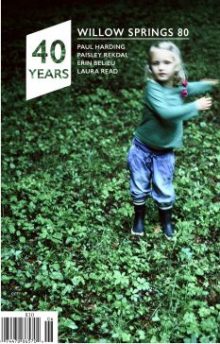

Photo Credit: Trane Devore

THE SPEAKERS IN PAISLEY REKDAL’S POEMS are often observers—drawing connections between the private and the personal, the historical, mythological, and scientific. Her lyricism and her combination of loose, free verse and structured, traditional forms come together to emphasize the slippage between fact and fantasy, old myths and new. In a review of Imaginary Vessels for the Los Angeles Times, Craig Morgan Teicher writes that Paisley Rekdal is “a poet of observation and history, one who carefully weighs the consequences of time. She revels in detail but writes vast, moral poems that help us live in a world of contraries in which ‘we hold still for the camera, believing / it will shore up time, knowing it won’t.”‘

Paisley Rekdal is the author of five books of poetry, most recently Imaginary Vessels (Copper Canyon Press, 2016) and Animal Eye (University of Pittsburgh, 2012), a book of essays, The Night My Mother Met Bruce Lee (Pantheon Books, 2000), and a hybrid genre, photo-text memoir entitled Intimate (Tupelo Press, 2012). Her book-length essay, The Broken Country: On Trauma, a Crime, and the Continuing Legacy of Vietnam, is forthcoming from University of Georgia Press in September 2017. She’s been awarded an NEA Fellowship, a Fulbright Fellowship, the Laurence Goldstein Prize, two Pushcart Prizes, and the 2011-2012 Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship.

Newly appointed as Utah Poet Laureate, Rekdal is invested in exploring humanity in all its complexities. She shies away from nothing: racism, sex, violence, religion, death, and all the intersections therein. Her voice is clear and original, allowing her to navigate through thought and emotion with relative ease. To read her work is to engage in a conversation about compassion and self-reflection that goes beyond the page. We met with her at the AWP Conference in Washington, DC, where we talked about ethical memory, World of Warcraft, and the failure of the American Dream.

ALIA BALES

Your work straddles lyric and narrative. What do you see as the role of narrative in poetry?

PAISLEY REKDAL

A lot of people have said I’m a narrative poet, and they don’t mean that in a good way. Narrative is not hip right now, and I take that as a formal challenge to be even more narrative. My newest project is a rewriting of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, taking several of his major myths and reworking them. It’s not a one-to-one translation where the gods come down and are made more contemporary by wearing Nikes. I’ve seen a lot of those reworkings, the kind that make the formal innovation Ovid was working with glib. I want to figure out what the myth is about, then reset it in a completely different contemporary setting. For instance, in the Tiresias myth, Tiresias lived as a woman and a man. I retell this story as a mother who has breast cancer and a daughter who is going through gender reassignment surgery. Both are trying to figure out, am I entirely myself now? Another story involves Io the young woman raped by Zeus and changed into a cow. In my story, she is a woman who ends up as a quadriplegic stuck in a body she doesn’t understand anymore.

Narrative allows me to do that. Narrative gives me characters. But writing a narrative poem is not natural to me. I have moments that seem narrative. But if you’re doing a narrative poem in the way that Ovid was thinking of a narrative poem, really telling a story, suddenly you are thinking of time very differently. You’re bringing in plot and foreshadowing. You’re thinking like a fiction writer.

I learned the difference between narrative and lyric in a pedagogy class with my graduate students, a bunch of fiction writers and a bunch of poets. We were reading a James Tate poem a student brought in to show us that poets can write prose. He said, “This is like a short story.” And the short story writers went insane. “This is not a short story at all,” they said. But the poets thought it read like a short story because there’s character. Something happens to that character, something else happens to that character. The end. The fiction writers said it was not a short story because there was no reason for anything. In fiction, there’s a cause-effect relationship. In poetry, there is no necessary cause and effect. Something happens, something happens, something happens, something happens. The cause and effect, if you will, is the resonance between the images. But that is not cause and effect. When you are writing a narrative poem, you have to think about psychological cause and effect. This happens, thus they start to feel this way, thus they act that way. It changes the nature of the poem entirely. A lot of the time we call a poem narrative simply because it has a character and the character says something or does something. Oftentimes though, the poem disrupts the very idea of what a narrative actually is.

BALES

Many of your poems are interested in, to quote Ovid, “bodies changing into other bodies.” For example, the “Epithalamium” sequence in Six Girls Without Pants. How are you engaging the Metamorphoses and this concept?

REKDAL

One continuing obsession in my work is about this nature of change. This whole book is about questioning the nature of change. What’s fascinating about Ovid’s Metamorphoses is that there is no consistent answer. Many people think change is only a form of punishment in that book. People become animals because they behave badly. Change is metonymic, it becomes the emblem of your past behaviors. If you are a greedy person, all you do is eat later on. Eat yourself to death. If you’re Acteon, a hunter, you turn into a deer and are torn apart by dogs. But there are a lot of people who change for the better. Like Baucis and Philemon in Imaginary Vessels. They get change that is not a punishment. In fact, change was the reward. You did good and you want to live and die together, so you will turn into an ever-blooming myrtle. Ovid himself changes the nature of change from story to story to story. I love that.

CHRIS MACCINI

In Imaginary Vessels you inhabit various personas, including Mae West’s. What do you see as the limitations and opportunities of personification?

REKDAL

The limitation is that it’s still you, as much as you’re performing as somebody else. Those Mae West sonnets are unusual for me because I wrote all of them, except two or three, using only letters that appear in the opening line of the poem. So there’s a formal limitation that is not obvious, but it’s something that registers sonically over time as a way of enacting and pointing out the real delight of her humor to me—which is wordplay. She used to compare herself to Shakespeare, which is absurd, because she’s not a Shakespearean writer, though she was obviously committed to wit. There’s a high level of verbal play in her one-liners and humor, and that was one of the opportunities for me to figure out a formal way to reenact voice and a persona. The idea of these sonnets was also to be sort of ossifying—they’re so trapped in their wordplay that they don’t open up in ways I would more naturally like. One of the things I love about persona poems is they allow you to imagine another character, but they also push you to figure out your own limitations as a thinker and a writer.

MACCINI

Is there anything that the persona frees you up to do? Do you find you’re able to explore different ideas or themes?

REKDAL

What it frees me up to do—especially in the “Shooting the Skulls: A Wartime Devotional” sonnet sequence—is make an almost didactic move. Several of those sonnets talk back to me and sort of say, “Why are you overlaying your family’s narratives and wars onto people who had nothing to do with those wars?” I was writing those sonnets and thinking what it was to capture someone’s individuality once it’s been lost. Talking back in a persona allowed me to point out that ethical problem. You can’t just transfer your emotions onto something and have that not be another form of erasure. The fact is, those bodies that were disinterred from the Colorado State Mental Institution, they’re gone. Those photographs were fascinating because they’re trying to reclaim individuality to these people and give them a sense of humanity.

Whenever you have a representation, you have a fantasy, you have an idea of what that person is or is not supposed to be. There is no reclamation, there is only the fantasy of intimacy, the fantasy of seeing and reclaiming and getting back to an original lost body. That’s what those moments of talking back offer, an ethical nudge to say, yeah, you think you’re doing that, but you just made another erasure.

I was reading the forensic archaeologist Shannon Novak’s work when I was working on those sonnets. She has this great essay about the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which happened in Utah about a century and a half ago and is still debated today. Mormon settlers slaughtered a wagon train party headed west, and covered it up as a Native American massacre. The church recovered the bones and bits of garments, buttons, pieces of shoe leather, and returned them to people they think of as the descendants. And people started to—even though they had no way of proving these buttons were from their grandmother or great-grandmother—treat them with reverence and assign them a relic status. There was a way in which they transferred all of their sense of historical trauma onto bodies that may or may not even belong to them.

What Novak talks about is a transference of emotion onto different objects. I thought that was fascinating but also disturbing. A lot of people have traumatic narratives within their family stories or their own lives and we don’t necessarily have the physical evidence of them. In fact, memorials work on that level, which is why we go to the Washington Monument, or the Lincoln Memorial. We don’t have attachment to them personally, but we transfer our emotional ideas upon these cultural icons, these eulogized sculptures. In lieu of a body, we create bodies.

BALES

In The Night My Mother Met Bruce Lee, you include two versions of how your grandfather acquired his laundromat. In your mother’s version, he received it for safekeeping from a Japanese neighbor interned during World War II. But according to other family members, he purchased it. You wrote, “If I have children I will tell them my mother’s story about Gung Gung’s laundromat,” instead of what actually happened. Why?

REKDAL

I’m finishing a book, The Broken Country, which collects oral histories from Southeast Asian refugees in post-1970 America. And there, the importance for me was facts, to get these people’s narratives right and to not indulge in fantasy. But one of the things I found fascinating is how to a certain extent a traumatic narrative is also a fantasy narrative.

The problem of narrative is that it is constructed event—it always has beginning, middle, and end. The perfect narrative has a sense of resolution. The essay about my grandfather was about that fantasy of narrative. What does the narrative offer us? Closure. Out of a damaging set of circumstances, my family came to the United States, and my grandmother would never speak about what happened to the family, the racist things I know she experienced. She’d be mortified that I’m telling everybody everything all the time. So that fantasy construction is in some ways an emotional connection with my grandmother, a healing, where people can all get along.

America is a place of opportunity. America is a place of cross cultural connection. America is a place where a bad past can be magically erased or eased over in a kumbaya way. And the reality is that that isn’t true. So there is something beautiful about telling that story. When I wrote that essay, I thought that if l had children, I would tell that story over and over to give them a sense of hope. Now I think I would tell both versions. Partly because the facts are in dispute. My grandmother has many reasons to want to lie about that story. She hated Japanese Americans, she hated Japanese people. And my grandfather hated the English. So there was no sense of historical feeling there at all.

MACCINI

Why do you think she clung to that narrative even though it went against what she was comfortable with?

REKDAL

My grandmother never clung to that narrative—my mother did, I think because that’s the assimilation story, the story of America we’ve been told over and over, and it’s an attractive one. Who doesn’t want to believe, at some level, whether it’s a salad bowl or a melting pot, that there’s a possibility of entering and assimilating—And I don’t even like that word—into American culture and being a deep part of it and not being the outsider? I think that’s what that story is about: how two different types of outsiders use the system to their advantage.

That fantasy about becoming American is powerful because it’s terrifying. You can spend your life in a country and then be told you’re not one of us and you never were and you didn’t realize it. You’ve been going along fine for a time and then someone is like, “Where are you from?” or “Go back to your country.” And you’re like, “No thank you, I’ve been here the whole time. This is my country.” That sense of being deeply franchised in America is a real longing and it’s not to be taken lightly.

MACCINI

In The Night My Mother Met Bruce Lee, you write about tensions you feel with your racial identity in various countries, but it seems like the place you feel the most discomfort is in the United States, when you travel to the South, and in Seattle growing up. Is there something about America that makes it more uncomfortable than a foreign country?

REKDAL

When you’re in a foreign country, you’re prepared to be an outsider, but when you’re in your own nation you’re not. That’s what makes it uncomfortable. What was funny to me living in Korea, spending time in Japan, traveling to China, and, recently, living in Southeast Asia is how familiar some of the racial and gender stereotypes are. It’s not as if Americans are the only ones who have them. It turns out you can find them everywhere you go because of our media. We’ve exported so many things. In those countries, they want people to be lighter skinned, they want women to have certain eye shapes, to be a certain physical size. They’re just more open about it, in a weird way. Whereas in America, I think there is an emphasis on being polite and hiding.

That’s why this election—for me at least, and for many people—was deeply unsettling, because you think, after eight years, we haven’t moved the needle more significantly. When you hear these things being said—probably not representative of all Trump voters, I understand that—but they say, “Finally we can say what we’ve always wanted to say” and it’s one of those ugly, ugly moments where you’re like, “Is this really what you’ve always been thinking?” That’s what makes it uncomfortable in America. And maybe it’s also some level of hope, to say that because I’ve grown up with these people—half my family is white—why would I assume that’s how they feel about me?

In the Atlantic article that Ta-Nehisi Coates did with Obama, he makes a comment that Obama’s biracial background might have made him not as good about fighting some things, like he didn’t understand the depth of certain white anger and anxiety around African Americans.

MACCINI

Because half his family is white?

REKDAL

Right, and of course they’re going to treat him well. Of course they’re going to love him. And he might see some level of racism, but it’s going to be tempered by the fact of his presence. It was the same with me. Being biracial gives you a fascinating insight into the way people will behave, but at the same time there are ways in which you might not see fully how bad it can be.

MACCINI

In his Willow Springs interview, Thomas Lynch said, “The reason poets aren’t read is because we don’t hang them anymore.” He goes on to describe an obligation he feels that artists, and poets in particular, should be engaged in political discourse. Do you feel that obligation?

REKDAL

What I find hard about that question is that I don’t know what we mean by political. People can look at Adrienne Rich and say that is political writing, they can look at some Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath and say that is political writing. They can look at Patricia Smith, they can name a dozen writers and immediately point out what’s political writing. But the question is: Is it political writing because of the bodies that have written the poems? Or is it the subject matter? Or is it a combination of both? Because one could make the argument that all of us are political writers.

Maybe narrative is a political act because you’re writing a narrative poem that is reaching a lot of people, and it describes your own existence that has not previously been described before. That’s what Adrienne Rich’s target was, that political act. But I really don’t know what people mean by “political poem” anymore.

BALES

In your Fogged Clarity interview, you said you thought that if you were to have an honest discussion about some political things in a public sphere that maybe poetry isn’t the best way to do that because it limits the conversation. You went on to argue that narrative in poetry is a political act in itself.

REKDAL

That’s me trying to work out the definition of political. Because if the political is ultimately an argument we need to make about policy, then poetry is a terrible place to do that. First of all, the audience is limited and second of all, didactic verse still exists—it’s just not a lot of people want to read it, and for good reason. But oftentimes poems rely on an engagement with the world, of a particular person in the world, and that person’s experience in the world. In that sense, a poem is always about change, and a didactic political piece of writing can’t be about change. You’re arguing from a fixed position, and that’s propaganda, so that’s why it doesn’t work for me as a poem.

Going back to Lynch’s argument, a poem relies on complexity. It’s not that political thought doesn’t depend on it, but that political writing has to make an argument. Political thinking can be complex, and in that sense we could re-frame the question to say, “In what ways can poems enact political thinking?” We see hundreds of examples because we see people engaged with the world and engaged with ideas that are not fixed positions, and they are working toward and through difficult ideas. Patricia Smith has a wonderful poem written in the voice of a skinhead, and it’s not an easy poem. It’s not what you think. It’s not an automatic Nazi salute, Sieg Heil. There’s complexity.

KIMBERLY POVLOSKI

You do a lot of research in your work—historical and scientific. What’s the difference between truth and fact, and what’s poetry’s role in that discussion?

REKDAL

Poetry is all truth and very little fact, unfortunately. Fact is normally in the realm of journalism, but there is an ethical component to that question—when poetry relies on truth, oftentimes facts will change around time, will change around events. But it becomes problematic when you’re dealing with people who have been de-voiced. There is an ethical problem at the heart of the “Shooting the Skulls” sequence.

In his book, Memory, History, Forgetting, Paul Ricœr talks about ethical memory, which is essentially the attempt to try to remember all of the people who normally become voiceless in traumatic conflict. He himself was interned at a concentration camp during World War II, so he was generally speaking about wartime conflicts and how we think about them and memorialize them. We think about soldiers, but we don’t think about the women who were raped. We don’t think about the children who died. We don’t think about the descendants of the people who survived the war. We don’t think about the disabled. We don’t think about the mentally ill. We don’t think about the illiterate. We don’t think about the poor. His idea about ethical memory is that we need to reclaim as many of these voices as possible.

When a poem goes for truth, one question you need to ask is, does it reclaim or erase or continue to forget certain existences? Some people are able to speak for themselves and some people aren’t. Forgetting is a political act. We don’t memorialize or remember certain people, and we essentially continue to erase them because it benefits another narrative.

Narrative is ultimately a political statement too, if you think about who gets written into a narrative and who gets taken out. Going back to the question regarding truth and fact, I would never ignore facts in a poem if they speak to an existence that I don’t want to see because it doesn’t suit my narrative. There are facts that matter more than others, and to continue to ignore certain facts only to back up your personal story can become problematic. At the worst, it continues to erase real historical people that had very particular meanings to their lives. At the best, it will highlight that you’re only using history as a sort of recitation of your own awesomeness.

MACCINI

Do you see truth as an emotional reality and facts as objective reality?

REKDAL

Facts are objective, exactly. If handled badly, you can overload anything with facts and it becomes about showing off—I know all this stuff and you don’t. And then you lose the line, the sense of music. In some ways I’m not going to have a good answer to this question because some part of this is instinctual. You don’t know why there is a connection, but you’re researching and you start writing, and you free write, and you put things together, and you take notes, and suddenly you’re like, that’s what I’m interested in, that’s what I’m talking about.

Why did I become fascinated with the photographs of Edward Sheriff Curtis? There was nothing on the surface except that they’re beautiful. But I kept going back and back and the more I read about him, the more I realized he’s just anxious about modernity. The project looks like it’s about American Indians but it’s actually about whiteness. That’s where research helps. The more questions you ask, the more likely you are to realize something about what you’re examining.

But the other thing I rely on to balance things is music. Poetry has to sound good. If you’ve got a lot of facts, they don’t tend to sound good. “Five million people died in the Johannesburg mines” is a really hard line to scan. I spend a lot of time reading drafts out loud, making sure they sound beautiful. To a certain extent, I rely on the music to tell me there’s something wrong here. Whether it’s intellectual or in terms of the image or whatever, something is wrong here, so I can circle it and go back.

BALES

Is that only with poetry, or do you do that with prose as well?

REKDAL

It’s only with poetry because—and this is terrible to say—I don’t care about prose. To me, it’s the dumping ground. If I have other things I have to get to, I’ll put that in prose because I don’t care if it sounds as pretty. It’s not like I don’t work on the sentences. I just don’t care as much.

MATTHEW MAPES

What about other forms? You put a lot of work into the blog you kept while traveling through Southeast Asia. It felt like an essay. How does working online, in Facebook, Twitter, blogs, etc. work into your view of literature, given the new spaces we have to write in the world?

REKDAL

You’re right about the blog—at some point it became exhausting because I had to keep the blog, but I was writing it like an essay I would publish in a magazine. I also edit and work with the website, Mapping Salt Lake City. One of the things I learned is that you can’t just do a one-to-one transference. Certain material works better on the internet. We read differently online. We have that great back end feature where you can see how many people clicked on a piece and how long they stayed. Longer form journalism, longer form essays, no one stays on them for long. Everyone wants pithy, two hundred, maybe five hundred words, short sentences, very direct. And it sounds obvious, but that was eye opening to me. I should have known that. I work in poetry and I work in nonfiction, and there are things that I know—that’s an essay and that’s a poem. You feel it instinctively. You know the form demands different kinds of reading experiences and different kinds of language.

MACCINI

Does that relate to how you said you don’t care about prose? Is it something you don’t engage with on an artistic level?

REKDAL

This is probably my failing, because every prose writer in America would be like, “Fuck you. This is art!” And I would have to say the same thing. The arguments I made suggest there is an art to digital writing too. I have not been taught to respect it. But there’s a formal quality to it. Twitter, say what you will, is a form of writing. A Facebook post is a form of writing. We may not take it seriously, but they’re all forms of expression.

My first training was not as a creative writer, it was as a medievalist. I sometimes think how amazing it would be to have had medieval Twitter, because when you’re doing research into the medieval period, you’re so limited by the text. There’s just not a lot of material. One of the great things about Twitter and Facebook and blogs is that they form an incredible historical record that’s constantly evolving. If you were an historian coming back and trying to figure out what 21st century America was like, you would have records that no other period of history has. The ability of people to express themselves like that is fantastic.

That’s one of the reasons I wanted to do a website for Mapping Salt Lake City and not a regular book. Once you’ve got a book, you’ve got an editing process and selection process. Certain voices come in because you want it to sound a certain way. The internet works against that—it’s community. But what I also learned is that there’s a class based privilege on the internet. You and I, we go on the internet and we’re there for hours, buying things and reading blogs and Twittering and Instagramming. But a lot of communities go to the internet because they’ve got to get health services, they’ve got to get job information. I’m in, I’m out, boom. They don’t play there. Their reading and writing experience on the internet is different. All of these things came up while writing the blog. And the blog finally killed me. I got midway through my time in Vietnam and thought, oh my god, just take a break. And then I didn’t go back. But it was a lot of fun too, the instantaneous reactions. People would send me emails like, “I love that piece.” That never happens. It was satisfying.

MAPES

How do you think the growing access to the internet, and the subsequent shrinking of the world has affected marginalized voices? Has it given them a chance to come out? Or has it given them more places to be hidden?

REKDAL

My suspicion would be a little of both. There are always going to be the outliers that learn how to use technology for their benefit. But one of the things that globalism has taught us is that people don’t necessarily like to be connected—maybe because it’s not that everybody is connected in their individuation; we’re connected via capitalism, too. So it’s not just that the internet allows for freedom of individual expression—it’s still within a certain type of economy of thought and self-expression based on Western values and capitalistic practices.

Have you heard about gold farmers? World of Warcraft is this endless game, but you can skip levels if you have gold that you can buy new weapons with. Rich players, mostly in the West, don’t want to go through all the levels. So they purchase gold. There were a couple communities in China where people were playing 24/7, just making gold, and selling it for real money online to players in the West so that they could skip ahead. Here’s leisure time of the West capitalizing on Chinese production and labor.

In Tung-Hui Hu’s book, A Prehistory of the Cloud, he talks about all these ways in which digital leisure time involves a lot of invisible capital and production. The reason our Facebook feeds are free of pornography and beheadings is because people in the Philippines watch animal torture and child pornography and the worst of humanity eight hours a day to scrub it—no algorithm can actually determine with 100 percent accuracy what is bad and what is good. People are getting traumatized in the second and third world so we can go through our feed and not see that stuff. When we’re talking about whether the internet opens up the world or just re-marginalizes the same voices, I think it does a bit of both. If you’re a rich Chinese person in Hong Kong, you’re not having these problems either. But if you’re poor and you have access to the internet and you figure out how to use it in certain ways, your labor might go into this.

I lived in Hanoi, where you can’t get Twitter, you can’t get Facebook, but everybody has it anyway because they get a VPN. You go into a café and see everyone on their computers with their VPNs. Are they reading The Guardian? The New York Times? No. They’re on Facebook, scrolling, looking at ads, which produces money for the West. Here’s a communist nation full of people who are entering a capitalist economy because they want to be online. This has nothing to do with digital expression, but someone will always take advantage of someone else. And it works both ways. It is both a liberating experience but also a reinforcement of the same things that are going on.

MACCINI

Can you talk about the ekphrastic impulse in your work? I’m thinking of the way the text in Intimate responds directly to the photographs of Edward Sheriff Curtis.

REKDAL

For me, poetry and photography are similar media. They’re static representations of a moment. And they may represent and create multiple emotions, changeable complex emotions, but they’re highly artistic, highly crafted, highly manipulated moments in time. I use the poems as my own photographs, basically. Sometimes a documentary photograph in Intimate has a distant, if not nonexistent, relationship to the prose that accompanies it. I wanted that interesting way in which we read the photograph one way, we read the text another way, and then we see them together and think, wow, that’s a completely different way of moving these against each other.

MACCINI

You said you’re creating a third art object, which exists within the reader—

REKDAL

Only within the reader. I have ideas of what that object should be. There’s a reason why I put this photograph next to this thing, but the resonance that I hope the reader experiences may not entirely exist. Maybe there’s a possibility for it.

The reader is always the unknown. Sometimes you’ll get the reader you’ve always wanted—which is you. And they’re like, oh my god, you’re brilliant, I totally see everything you were doing, I get it. And then you get the other readers, which is most people, and they’re like, uh, what? But they end up sometimes having rich reading experiences in directions, where you’re like, okay, have fun there, I have no idea how you got there, but I’ll accept it because that’s reading. Reading triggers the imagination, it triggers memories and associations, and those are impossible to pare back. And you don’t want to.

MACCINI

Does that triangulation of poem, photograph, and reader work in a different way than, say, an essay?

REKDAL

I can only point to the work of other writers to answer that question. Because I don’t necessarily know if it does in my work. I was influenced by W.G. Sebald and then Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. The ways they use photographs are exactly the ways I wanted to use photographs, where there is that triangulation effect. I cheat, though. In my two books, I have beautiful photos. But if you read Sebald’s work, those photos are incredibly dull. If you were just flipping through them, you would pass them up. They don’t register. And oftentimes they’re badly reproduced, deliberately so. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, same thing. Badly reproduced photos, oftentimes of moments that look like they could be meaningful, but stripped of context. And her text refuses to give you context. Sebald does that too. If you took these photos outside of the context of the text he produces, you’d say, “These are the world’s worst vacation photos.” But when you put them next to text, suddenly we’re talking about the decay of Victorian values as World War I and World War II are looming on the horizon. An innocent beach scene becomes the Holocaust. It’s amazing. He infuses history into photos that are absolutely devoid of any sense of time. Cha does the same thing with her photographs of traumas in Korean history. You’ll see people looking into the distance screaming. But you can’t see what they’re seeing. You have no idea if they’re at a game and they’re shouting excitedly or they’re watching a horrific massacre. That sense of the information being off-screen is terrifying and creates a sense of unease. It disrupts this sense of history. Both Cha’s book and Sebald’s work are trying to reclaim moments of history. Sebald is pointing out what we normally forget, what we normally write over, and trying to bring those to the forefront, to make us see what we have suppressed. In Cha’s case, she’s like, you may think you know, but I’m going to suppress what you want to see, all the time, until it’s actually the opposite. I love their work.

MAPES

That triangulation effect relies on the reader to internalize whatever they are taking in. What is the relationship between the poem and the reader?

REKDAL

That goes back to what I said about ethical memory. At the heart of that idea is an impossibility. The desire to represent the world in language is an attempt to get closer to the reader. To have an empathetic experience, the reader imagines that they’ve walked a mile in your shoes. It is an attempt to force the reader to have a certain emotional response. So in one way, it is this intimate and emotional bid that the artist is making. But there is selfishness and egotism that can never be denied. The persona poem is still the writer. The representation has a failure built into it. There’s always a limitation to what we can express and what we can hear and what we can imagine. But that doesn’t mean that you can’t make an attempt. If you make no attempt whatsoever, there’s no communication at all, no possibility of intimacy.

That’s what fascinates me about the nature of intimacy. You’re backing away as much as you’re coming close. What I love about photography is that it purports to document the real world. This thing happened to me, and I saw it. But every photograph is posed. Every photograph is framed. In every photograph, there is more that you don’t see than you do see. As soon as you aim the camera, you’ve said I’m not looking at that. A poem is the same. As soon as you say this fits, something else does not. And so it is not documentary, not an accurate representation of the world. We are more likely to say that is true about a poem. We recognize that it’s highly manipulated. But a lot of people still want to see the photograph as the actual thing. Narrative and lyric poems make an interesting bid, because they are the more realistic forms of poetry. There is a suggestion that the reader is going to say that this happened to the writer. I now know who this person is. That is a mistake. The form suggests transparency, but it is just as opaque as anything else.

BALES

In your poem, “The History of Paisley,” you turn the lens onto yourself in a way that’s accommodating to your readers. I’m wondering how you look at yourself with such clarity.

REKDAL

That’s assuming that I’m right, that I’m looking at myself clearly. Because I could totally be making shit up. I’m writing about myself, but that doesn’t mean it’s accurate. It’s a performance of myself that appeals to readers because it hits certain notes of humility and charm. I’ve read lots of poems from horrendous people I’ve known personally. We all know horrific people who are writing wonderful poems. I don’t think just because you like the persona that you like me.

BALES

So when you write about yourself, it is a persona as well? How aware are you of that?

REKDAL

This is important with memoir. Oftentimes when you are writing about things that happened, other people look bad. So it’s your turn. You have to turn the gaze around and let yourself look bad. That’s a formal device. But it’s absolutely necessary as a bid to the reader to say, “You can trust what’s coming out of my mouth.” And it works in poetry too. When the self behaves badly, it can do one of two things. If the self behaves too consistently badly, people may be horrified and walk away. But if the self behaves just badly enough, there is a moment of “authenticity,” which is funny because it’s a performance. It is always a performance.